Chapter 4 Model-based Planning and Optimization

In Chapter 1, we studied tabular MDPs with known dynamics where both the state and action spaces are finite, and we saw how dynamic-programming methods—Policy Iteration (PI) and Value Iteration (VI)—recover optimal policies.

Chapters 2 and 3 generalized these ideas to unknown dynamics and continuous spaces by introducing function approximation for value functions and policies. Those methods are model-free: they assume no access to the transition model and rely solely on data collected from interaction.

This chapter turns to the complementary regime: known dynamics with continuous state and action spaces. Our goal is to develop model-based planning and optimization methods that exploit the known dynamics to compute high-quality decisions efficiently.

We proceed in three steps:

Linear-quadratic systems. For linear dynamics and quadratic stage/terminal rewards (or costs), dynamic programming yields a linear optimal policy that can be computed efficiently via Riccati recursions. This setting serves as a tractable, illuminating baseline and a recurring building block in more general algorithms.

Trajectory optimization (TO) for nonlinear systems. When dynamics are nonlinear, we focus on planning an optimal state–action trajectory from a given initial condition, maximizing the cumulative reward (or minimizing cumulative cost) subject to dynamics and constraints. Unlike RL, which seeks an optimal feedback policy valid for all states, TO computes an open-loop plan (often with a time-varying local feedback around a nominal trajectory). Although less ambitious, TO naturally accommodates state/control constraints—common in motion planning under safety, actuation, and environmental limits—and is widely used in robotics and control.

Model predictive control (MPC). MPC converts open-loop plans into a feedback controller by repeatedly solving a short-horizon TO problem at each time step, applying only the first action, and receding the horizon. This receding-horizon strategy brings robustness to disturbances and model mismatch while retaining the constraint-handling benefits of TO.

We adopt the standard discrete-time dynamical system notation \[\begin{equation} x_{t+1} = f_t(x_t, u_t, w_t), \tag{4.1} \end{equation}\] where \(x_t \in \mathbb{R}^n\) is the state, \(u_t \in \mathbb{R}^m\) is the control/action, \(w_t \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is a (possibly stochastic) disturbance, and \(f_t\) is a known transition function, potentially nonlinear or nonsmooth. The goal is to find a policy that maximizes a sum of stage rewards \(r(x_t,u_t)\) and optional terminal reward \(r_T(x_T)\). We will often use the cost-minimization form \(c = -r\). State and action constraints are written as \[ x_t \in \mathcal{X}, \qquad u_t \in \mathcal{U}. \]

4.1 Linear Quadratic Regulator

In this section, we focus on the case when \(f_t\) is a linear function, and the rewards/costs are quadratic in \(x\) and \(u\). This family of problems is known as linear quadratic regulator (LQR).

4.1.1 Finite-Horizon LQR

Consider a linear discrete-time dynamical system \[\begin{equation} x_{k+1} = A_k x_k + B_k u_k + w_k, \quad k=0,1,\dots,N-1, \tag{4.2} \end{equation}\] where \(x_k \in \mathbb{R}^n\) the state, \(u_k \in \mathbb{R}^m\) the control, \(w_k \in \mathbb{R}^n\) the independent, zero-mean disturbance with given probability distribution that does not depend on \(x_k,u_k\), and \(A_k \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}, B_k \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times m}\) are known matrices determining the transition dynamics.

We want to solve the following optimal control problem \[\begin{equation} \min_{\mu_0,\dots,\mu_{N-1}} \mathbb{E} \left\{ x_N^\top Q_N x_N + \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} \left( x_k^\top Q_k x_k + u_k^\top R_k u_k \right) \right\}, \tag{4.3} \end{equation}\] where \(\mu_0,\dots,\mu_{N-1}\) are feedback policies/controllers that map states to actions and the expectation is taken over the randomness in \(w_0,\dots,w_{N-1}\). In (4.3), \(\{Q_k \}_{k=0}^N\) are positive semidefinite matrices, and \(\{ R_k \}_{k=0}^{N-1}\) are positive definite matrices. The formulation (4.3) is known as the linear quadratic regulator (LQR) problem because the dynamics is linear, the cost is quadratic, and the formulation can be considered to “regulate” the system around the origin \(x=0\).

The Bellman Optimality condition introduced in Theorem 1.1 still holds for continuous state and action spaces. Therefore, we will try to follow the dynamic programming (DP) algorithm in Section 1.1.4 to solve for the optimal policy.

The DP algorithm computes the optimal cost-to-go backwards in time. The terminal cost is \[ J_N(x_N) = x_N^\top Q_N x_N \] by definition.

The optimal cost-to-go at time \(N-1\) is equal to \[\begin{equation} \begin{split} J_{N-1}(x_{N-1}) = \min_{u_{N-1}} \mathbb{E}_{w_{N-1}} \{ x_{N-1}^\top Q_{N-1} x_{N-1} + u_{N-1}^\top R_{N-1} u_{N-1} + \\ \Vert \underbrace{A_{N-1} x_{N-1} + B_{N-1} u_{N-1} + w_{N-1} }_{x_N} \Vert^2_{Q_N} \} \end{split} \tag{4.4} \end{equation}\] where \(\Vert v \Vert_Q^2 = v^\top Q v\) for \(Q \succeq 0\). Now observe that the objective in (4.4) is \[\begin{equation} \begin{split} x_{N-1}^\top Q_{N-1} x_{N-1} + u_{N-1}^\top R_{N-1} u_{N-1} + \Vert A_{N-1} x_{N-1} + B_{N-1} u_{N-1} \Vert_{Q_N}^2 + \\ \mathbb{E}_{w_{N-1}} \left[ 2(A_{N-1} x_{N-1} + B_{N-1} u_{N-1} )^\top Q_{N-1} w_{N-1} \right] + \\ \mathbb{E}_{w_{N-1}} \left[ w_{N-1}^\top Q_N w_{N-1} \right] \end{split} \end{equation}\] where the second line is zero due to \(\mathbb{E}[w_{N-1}] = 0\) and the third line is a constant with respect to \(u_{N-1}\). Consequently, the optimal control \(u_{N-1}^\star\) can be computed by setting the derivative of the objective with respect to \(u_{N-1}\) equal to zero \[\begin{equation} u_{N-1}^\star = - \left[ \left( R_{N-1} + B_{N-1}^\top Q_N B_{N-1} \right)^{-1} B_{N-1}^\top Q_N A_{N-1} \right] x_{N-1}. \tag{4.5} \end{equation}\] Plugging the optimal controller \(u^\star_{N-1}\) back to the objective of (4.4) leads to \[\begin{equation} J_{N-1}(x_{N-1}) = x_{N-1}^\top S_{N-1} x_{N-1} + \mathbb{E} \left[ w_{N-1}^\top Q_N w_{N-1} \right], \tag{4.6} \end{equation}\] with \[ S_{N-1} = Q_{N-1} + A_{N-1}^\top \left[ Q_N - Q_N B_{N-1} \left( R_{N-1} + B_{N-1}^\top Q_N B_{N-1} \right)^{-1} B_{N-1}^\top Q_N \right] A_{N-1}. \] We note that \(S_{N-1}\) is positive semidefinite (this is an exercise for you to convince yourself).

Now we realize that something surprising and nice has happened.

The optimal controller \(u^{\star}_{N-1}\) in (4.5) is a linear feedback policy of the state \(x_{N-1}\), and

The optimal cost-to-go \(J_{N-1}(x_{N-1})\) in (4.6) is quadratic in \(x_{N-1}\), just the same as \(J_{N}(x_N)\).

This implies that, if we continue to compute the optimal cost-to-go at time \(N-2\), we will again compute a linear optimal controller and a quadratic optimal cost-to-go. This is the rare nice property for the LQR problem, that is,

The (representation) complexity of the optimal controller and cost-to-go does not grow as we run the DP recursion backwards in time.

We summarize the solution for the LQR problem (4.3) as follows.

Proposition 4.1 (Solution of Discrete-Time Finite-Horizon LQR) The optimal controller for the LQR problem (4.3) is a linear state-feedback policy \[\begin{equation} \mu_k^\star(x_k) = - K_k x_k, \quad k=0,\dots,N-1. \tag{4.7} \end{equation}\] The gain matrix \(K_k\) can be computed as \[ K_k = \left( R_k + B_k^\top S_{k+1} B_k \right)^{-1} B_k^\top S_{k+1} A_k, \] where the matrix \(S_k\) satisfies the following backwards recursion \[\begin{equation} \hspace{-6mm} \begin{split} S_N &= Q_N \\ S_k &= Q_k + A_k^\top \left[ S_{k+1} - S_{k+1}B_k \left( R_k + B_k^\top S_{k+1} B_k \right)^{-1} B_k^\top S_{k+1} \right] A_k, k=N-1,\dots,0. \end{split} \tag{4.8} \end{equation}\] The optimal cost-to-go is given by \[ J_0(x_0) = x_0^\top S_0 x_0 + \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} \mathbb{E} \left[ w_k^\top S_{k+1} w_k\right]. \] The recursion (4.8) is called the discrete-time Riccati equation.

Proposition 4.1 states that, to evaluate the optimal policy (4.7), one can first run the backwards Riccati equation (4.8) to compute all the positive definite matrices \(S_k\), and then compute the gain matrices \(K_k\). For systems of reasonable dimensions, evalutating the matrix inversion in (4.8) should be fairly efficient.

4.1.2 Infinite-Horizon LQR

We now switch to the infinite-horizon LQR problem \[\begin{align} \min_{\mu} & \quad \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \left( x_k^\top Q x_k + u_k^\top R u_k \right) \tag{4.9} \\ \text{subject to} & \quad x_{k+1} = A x_k + B u_k, \quad k=0,\dots,\infty, \tag{4.10} \end{align}\] where \(Q \succeq 0\), \(R \succ 0\), \(A,B\) are constant matrices, and we seek a stationary policy \(\mu\) that maps states to actions. Note that here we remove the disturbance \(w_k\) because in general adding \(w_k\) will make the objective function unbounded. To handle \(w_k\), we will have to either add a discount factor \(\gamma\), or switch to an average cost objective function.

For infinite-horizon problems, the Bellman Optimality condition changes from a recursion to an equation. Specifically, according to Theorem 1.2 and equation (1.28), the optimal value function should satisfy the following Bellman optimality equation, restated for the case of cost minimization instead of reward maximization: \[\begin{equation} J^\star (x) = \min_{u} \left[ c(x,u) + \sum_{x'} P(x' \mid x, u) J^\star (x') \right], \quad \forall x, \tag{4.11} \end{equation}\] where \(c(x,u)\) is the cost function.

Guess A Solution. Based on our derivation in the finite-horizon case, we might as well guess that the optimal value function is a quadratic function: \[ J(x) = x^\top S x, \quad \forall x, \] for some positive definite matrix \(S\). Then, our guessed solution must satisfy the Bellman optimality stated in (4.11): \[\begin{equation} x^\top S x = J(x) = \min_{u} \left\{ x^\top Q x + u^\top R u + \Vert \underbrace{A x + B u}_{x'} \Vert_S^2 \right\}. \tag{4.12} \end{equation}\] The minimization over \(u\) in (4.12) can again be solved in closed-form by setting the gradient of the objective with respect to \(u\) to be zero \[\begin{equation} u^\star = - \underbrace{\left[ \left( R + B^\top S B \right)^{-1} B^\top S A \right]}_{K} x. \tag{4.13} \end{equation}\] Plugging the optimal \(u^\star\) back into (4.12), we see that the matrix \(S\) has to satisfy the following equation \[\begin{equation} S = Q + A^\top \left[ S - SB \left( R + B^\top S B \right)^{-1} B^\top S \right] A. \tag{4.14} \end{equation}\] Equation (4.14) is known as the discrete algebraic Riccati equation (DARE).

So the question boils down to if the DARE has a solution \(S\) that is positive definite?

Proposition 4.2 (Solution of Discrete-Time Infinite-Horizon LQR) Consider a linear system \[ x_{k+1} = A x_k + B u_k, \] with \((A,B)\) controllable (see Section 4.1.3). Let \(Q \succeq 0\) in (4.9) be such that \(Q\) can be written as \(Q = C^\top C\) with \((A,C)\) observable.

Then the optimal controller for the infinite-horizon LQR problem (4.9) is a stationary linear policy \[ \mu^\star (x) = - K x, \] with \[ K = \left( R + B^\top S B \right)^{-1} B^\top S A. \] The matrix \(S\) is the unique positive definite matrix that satisfies the discrete algebraic Riccati equation \[\begin{equation} S = Q + A^\top \left[ S - SB \left( R + B^\top S B \right)^{-1} B^\top S \right] A. \tag{4.15} \end{equation}\]

Moreover, the closed-loop system \[ x_{k+1} = A x_k + B (-K x_k) = (A - BK) x_k \] is stable, i.e., the eigenvalues of the matrix \(A - BK\) are strictly within the unit circle (see Appendix B.1.2).

Remark. The assumptions of \((A,B)\) being controllable and \((A,C)\) being observable can be relaxted to \((A,B)\) being stabilizable and \((A,C)\) being detectable (for definitions of stabilizability and detectability, see Appendix B).

We have not discussed how to solve the algebraic Riccati equation (4.15). It is clear that (4.15) is not a linear system of equations in \(S\). In fact, the numerical algorithms for solving the algebraic Riccati equation can be highly nontrivial, for example see (Arnold and Laub 1984). Fortunately, such algorithms are often readily available, and as practitioners we do not need to worry about solving the algebraic Riccati equation by ourselves. For example, the Matlab dlqr and the Python scipy.linalg.solve_discrete_are function computes the \(K\) and \(S\) matrices from \(A,B,Q,R\).

Let us now apply the infinite-horizon LQR solution to stabilizing a simple pendulum.

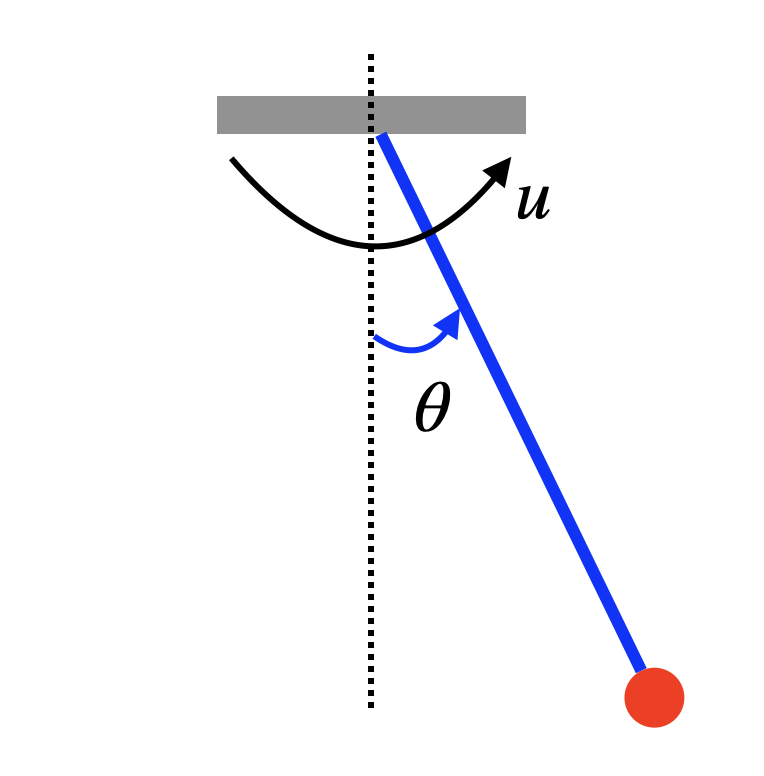

Example 4.1 (Pendulum Stabilization by LQR) Consider the simple pendulum in Fig. 4.1 with dynamics \[\begin{equation} x = \begin{bmatrix} \theta \\ \dot{\theta} \end{bmatrix}, \quad \dot{x} = f(x,u) = \begin{bmatrix} \dot{\theta} \\ -\frac{1}{ml^2}(b \dot{\theta} + mgl \sin \theta) + \frac{1}{ml^2} u \end{bmatrix} \tag{4.16} \end{equation}\] where \(m\) is the mass of the pendulum, \(l\) is the length of the pole, \(g\) is the gravitational constant, \(b\) is the damping ratio, and \(u\) is the torque applied to the pendulum.

We are interested in applying the LQR controller to balance the pendulum in the upright position \(x_d = [\pi,0]^\top\) with a zero velocity.

Figure 4.1: A Simple Pendulum.

Let us first shift the dynamics so that “\(0\)” is the upright position. This can be done by defining a new variable \(z = x - x_d = [\theta - \pi, \dot{\theta}]^\top\), which leads to \[\begin{equation} \dot{z} = \dot{x} = f(x,u) = f(z + x_d,u) = \begin{bmatrix} z_2 \\ \frac{1}{ml^2} \left( u - b z_2 + mgl \sin z_1 \right) \end{bmatrix} = f'(z,u). \tag{4.17} \end{equation}\] We then linearize the nonlinear dynamics \(\dot{z} = f'(z,u)\) at the point \(z^\star = 0, u^\star = 0\): \[\begin{align} \dot{z} & \approx f'(z^\star,u^\star) + \left( \frac{\partial f'}{\partial z} \right)_{z^\star,u^\star} (z - z^\star) + \left( \frac{\partial f'}{\partial u} \right)_{z^\star,u^\star} (u - u^\star) \\ & = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ \frac{g}{l} \cos z_1 & - \frac{b}{ml^2} \end{bmatrix}_{z^\star, u^\star} z + \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \frac{1}{ml^2} \end{bmatrix} u \\ & = \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ \frac{g}{l} & - \frac{b}{ml^2} \end{bmatrix}}_{A_c} z + \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \frac{1}{ml^2} \end{bmatrix}}_{B_c} u. \end{align}\] Finally, we convert the continuous-time dynamics to discrete time with a fixed discretization \(h\) \[ z_{k+1} = \dot{z}_k \cdot h + z_k = \underbrace{(h \cdot A_c + I )}_{A} z_k + \underbrace{(h \cdot B_c)}_{B} u_k. \]

We are now ready to implement the LQR controller. In the formulation (4.9), we choose \(Q = I\), \(R = I\), and compute the gain matrix \(K\) by solving the DARE.

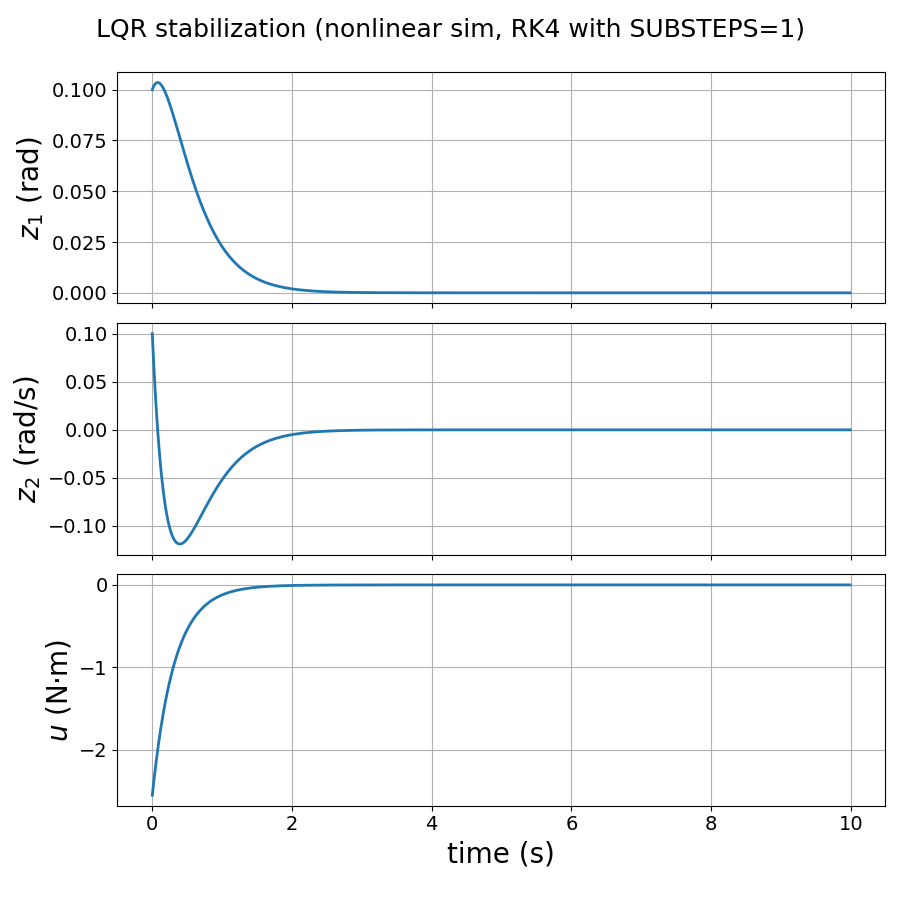

Fig. 4.2 shows the simulation result for \(m=1,l=1,b=0.1\), \(g = 9.8\), and \(h = 0.01\), with an initial condition \(z^0 = [0.1,0.1]^\top\). We can see that the LQR controller successfully stabilizes the pendulum at \(z^\star\), the upright position.

You can play with the Python code here.

Alternatively, the Matlab code can be found here.

Figure 4.2: LQR stabilization of a simple pendulum.

4.1.3 Linear System Basics

Consider the discrete-time linear time-invariant (LTI) system \[ x_{k+1}=Ax_k+Bu_k,\qquad y_k=Cx_k+Du_k, \] with \(x_k\in\mathbb{R}^n,\;u_k\in\mathbb{R}^m,\;y_k\in\mathbb{R}^p\).

We provide a very brief review of linear system theory to understand Proposition 4.2. More details can be found in Appendix B.

Stability. The autonomous system \(x_{k+1}=Ax_k\) is (asymptotically) stable if for every \(x_0\) we have \(x_k\to 0\) as \(k\to\infty\).

Equivalent characterizations.

\(A\) is Schur: all eigenvalues satisfy \(|\lambda_i(A)|<1\).

Lyapunov: \(\exists P\succ 0\) s.t. \(A^\top P A - P \prec 0\).

Controllability (reachability). The pair \((A,B)\) is controllable if for any \(x_0,x_f\) there exists a finite input sequence \(\{u_0,\dots,u_{N-1}\}\) that drives the state from \(x_0\) to \(x_N=x_f\).

Kalman controllability matrix. \[ \mathcal C \;=\; [\,B\; AB\; A^2B\;\cdots\; A^{n-1}B\,],\quad \text{\((A,B)\) controllable} \iff \operatorname{rank}(\mathcal C)=n. \]

Popov-Belevitch-Hautus (PBH) test. \[ \text{\((A,B)\) controllable} \iff \operatorname{rank}\!\begin{bmatrix}\lambda I - A & B\end{bmatrix} = n \ \text{for all}\ \lambda\in\mathbb{C}. \] It suffices to check \(\lambda\) equal to the eigenvalues of \(A\).

Observability. The pair \((A,C)\) is observable if the initial state \(x_0\) can be uniquely determined from a finite sequence of outputs (and known inputs), e.g., from \(\{y_0,\dots,y_{n-1}\}\).

Observability matrix. \[ \mathcal O \;=\; \begin{bmatrix} C \\ CA \\ \vdots \\ CA^{n-1}\end{bmatrix},\quad \text{\((A,C)\) observable} \iff \operatorname{rank}(\mathcal O)=n. \]

PBH test. \[ \text{\((A,C)\) observable} \iff \operatorname{rank}\!\begin{bmatrix}\lambda I - A^\top & C^\top\end{bmatrix} = n \ \text{for all}\ \lambda\in\mathbb{C}. \] Dual to controllability: \((A,C)\) observable \(\Leftrightarrow\) \((A^\top,C^\top)\) controllable.

4.2 LQR Trajectory Tracking

Classical LQR delivers an optimal linear state-feedback when dynamics are linear and the objective is quadratic. In many planning problems, however, we do not seek a single stationary feedback for all states but rather a local stabilizer around a given (possibly time-varying) trajectory—for instance, a motion plan from a trajectory optimizer or MPC’s rolling nominal (see Section 4.3). LQR Tracking (also called time-varying LQR, TVLQR) provides exactly this: a time-varying linear feedback that stabilizes the system near a nominal state–control sequence and rejects small disturbances.

Problem Setup. Let the nominal (i.e., ignoring the disturbance) discrete-time system be \[ x_{t+1} \;=\; f_t(x_t,u_t), \qquad t=0,\dots,N-1, \] and suppose we have a nominal trajectory \(\{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\}_{t=0}^{N-1}\) satisfying \[ \bar x_{t+1} \;=\; f_t(\bar x_t,\bar u_t). \]

Our goal is to design a controller that can stabilize the system with disturbance, i.e., \(x_{t+1} = f_t(x_t, u_t, w_t)\), around the nominal trajectory.

Towards this, we define deviations from the nominal trajectory as \[ \delta x_t := x_t-\bar x_t, \qquad \delta u_t := u_t-\bar u_t. \]

If the true system is linear time-varying (or we linearize a nonlinear system along the nominal), we obtain the deviation dynamics \[ \delta x_{t+1} \;\approx\; A_t\,\delta x_t + B_t\,\delta u_t, \quad A_t := \left.\frac{\partial f_t}{\partial x}\right|_{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)},\quad B_t := \left.\frac{\partial f_t}{\partial u}\right|_{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)}. \tag{4.18} \]

We penalize deviations with a quadratic cost \[ J \;=\; \delta x_N^\top Q_N \delta x_N \;+\;\sum_{t=0}^{N-1} \Big(\delta x_t^\top Q_t \delta x_t \;+\; \delta u_t^\top R_t \delta u_t\Big), \quad Q_t\succeq 0,\; R_t\succ 0. \tag{4.19} \]

LQR Tracking Algorithm. The tracking controller takes the affine form \[ u_t \;=\; \bar u_t \;-\; K_t\,(x_t-\bar x_t), \] where \(\{K_t\}_{t=0}^{N-1}\) are time-varying gains computed by a backward Riccati recursion on the deviation system (4.18) with cost (4.19).

From Proposition 4.1, we know the gains can be computed as follows.

Initialize at terminal time: \[ S_N \;=\; Q_N. \] For \(t = N-1,\,N-2,\,\dots,\,0\): \[\begin{equation} \begin{split} K_t &= \Big(R_t + B_t^\top S_{t+1} B_t\Big)^{-1} B_t^\top S_{t+1} A_t, \\[2mm] S_t &= Q_t \;+\; A_t^\top \!\Big(S_{t+1} - S_{t+1} B_t \big(R_t + B_t^\top S_{t+1} B_t\big)^{-1} B_t^\top S_{t+1}\Big) A_t. \end{split} \tag{4.20} \end{equation}\]

Given the gains \(\{K_t\}\), apply at runtime: \[\begin{equation} u_t \;=\; \bar u_t - K_t\,(x_t-\bar x_t), \qquad t=0,\dots,N-1. \tag{4.21} \end{equation}\]

The following pseudocode summarizes the algorithm.

Algorithm: LQR Trajectory Tracking (TVLQR)

Inputs: nominal \(\{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\}_{t=0}^{N-1}\), weights \(\{Q_t,R_t\}\), terminal \(Q_N\).

- Linearize along the nominal to get \(A_t,B_t\) via (4.18).

- Backward pass: compute \(K_t\) and \(S_t\) via (4.20).

- Apply feedback: \(u_t=\bar u_t - K_t(x_t-\bar x_t)\) as in (4.21).

Output: time-varying gains \(\{K_t\}\) giving a local stabilizer around the trajectory.

We now apply TVLQR to a vehicle trajectory tracking problem.

Example 4.2 (LQR Trajectory Tracking for Unicyle) We (i) define the dynamics in continuous and discrete time, (ii) specify a circular nominal trajectory, (iii) linearize the nonlinear dynamics along the nominal, (iv) state the deviation-cost weights \(Q,R\) (and terminal \(Q_N\)), and (v) list the experiment setup (discretization and horizon length).

Unicycle Dynamics (Continuous and Discrete).

State and input.

\[

x=\begin{bmatrix}p_x\\ p_y\\ \theta\end{bmatrix}\in\mathbb{R}^3,

\qquad

u=\begin{bmatrix}v\\ \omega\end{bmatrix}\in\mathbb{R}^2,

\]

where \((p_x,p_y)\) is planar position, \(\theta\) is heading, \(v\) is forward speed, and \(\omega\) is yaw rate.

Continuous time: \[\begin{equation} \dot p_x = v\cos\theta,\qquad \dot p_y = v\sin\theta,\qquad \dot\theta = \omega. \tag{4.22} \end{equation}\]

Discrete time (forward Euler with step \(h>0\)): \[\begin{equation} x_{t+1} \;=\; f(x_t,u_t) := \begin{bmatrix} p_{x,t} + h\, v_t\cos\theta_t\\[2pt] p_{y,t} + h\, v_t\sin\theta_t\\[2pt] \theta_t + h\,\omega_t \end{bmatrix}. \tag{4.23} \end{equation}\]

Nominal Trajectory (Circular Motion). We track a circle of radius \(R=\dfrac{\bar v}{\bar\omega}\) using constant nominal inputs \[\begin{equation} \bar u_t \equiv \begin{bmatrix}\bar v\\ \bar\omega\end{bmatrix},\qquad t=0,\dots,N-1, \tag{4.24} \end{equation}\] and generate the nominal state recursively under the discrete dynamics (4.23): \[\begin{equation} \bar x_{t+1} \;=\; f(\bar x_t,\bar u_t),\qquad \bar x_0 = \begin{bmatrix}R\\ 0\\ \frac{\pi}{2}\end{bmatrix}. \tag{4.25} \end{equation}\]

We define deviations from the nominal: \[ \delta x_t := x_t-\bar x_t,\qquad \delta u_t := u_t-\bar u_t. \]

Linearization Along the Nominal. Linearize (4.23) at \((\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\) to obtain the deviation dynamics \[\begin{equation} \delta x_{t+1} \;\approx\; A_t\,\delta x_t + B_t\,\delta u_t, \tag{4.26} \end{equation}\] with Jacobians (using \(c_t:=\cos\bar\theta_t,\ s_t:=\sin\bar\theta_t\)) \[\begin{equation} A_t \;=\; \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\Big|_{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & -h\,\bar v\,s_t\\ 0 & 1 & \ \ h\,\bar v\,c_t\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \qquad B_t \;=\; \frac{\partial f}{\partial u}\Big|_{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)} = \begin{bmatrix} h\,c_t & 0\\ h\,s_t & 0\\ 0 & h \end{bmatrix}. \tag{4.27} \end{equation}\]

Deviation Cost (Weights \(Q,R,Q_N\)). We penalize deviations with a quadratic stage/terminal cost \[ J \;=\; \delta x_N^\top Q_N\,\delta x_N \;+\;\sum_{t=0}^{N-1}\Big(\delta x_t^\top Q\,\delta x_t+\delta u_t^\top R\,\delta u_t\Big), \] using the weights: \[\begin{equation} Q=\mathrm{diag}(30,\;30,\;5),\qquad Q_N=\mathrm{diag}(60,\;60,\;8),\qquad R=\mathrm{diag}(0.2,\;0.2). \tag{4.28} \end{equation}\] These reflect a stronger emphasis on position tracking, a moderate penalty on heading error, and a mild penalty on control deviations from the nominal.

Experiment Setup.

- Discretization step: \(h = 0.02\ \mathrm{s}\).

- Horizon length: \(T_{\mathrm{final}} = 12\ \mathrm{s}\).

- Number of steps: \(N = T_{\mathrm{final}}/h = \mathbf{600}\).

- Nominal inputs: \(\bar v = 1.2\ \mathrm{m/s},\ \bar\omega = 0.4\ \mathrm{rad/s}\) (radius \(R=\bar v/\bar\omega\)).

- Initialization: the nominal starts at \(\bar x_0 = [\,R,\,0,\,\pi/2\,]^\top\); the actual system may start with a small offset (see code).

With \((A_t,B_t)\) from (4.27) and weights (4.28), the TVLQR backward Riccati recursion (Section 4.2) yields gains \(K_t\). We then apply the local feedback \[ u_t \;=\; \bar u_t - K_t\,(x_t-\bar x_t), \] to robustly track the circular nominal under small disturbances.

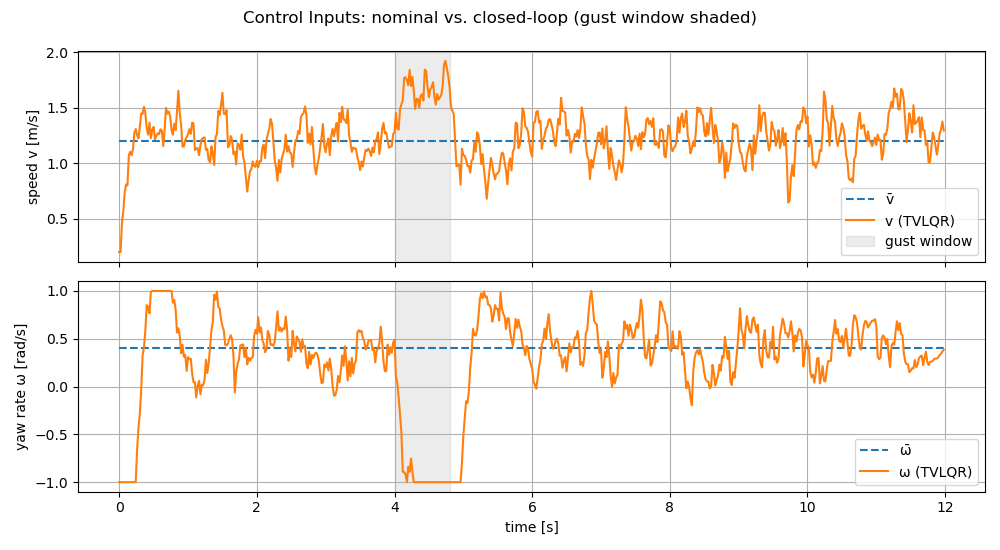

Disturbances. To test robustness, we inject additive process disturbances into the discrete dynamics: \[ x_{t+1} \;=\; f(x_t,u_t)\;+\; w_t,\qquad t=0,\dots,N-1, \] where \[ w_t \;=\; \underbrace{\eta_t}_{\text{i.i.d. Gaussian noise}} \;+\; \underbrace{g_t}_{\text{deterministic gust}}. \]

Small i.i.d. Gaussian process noise. We draw \(\eta_t \sim \mathcal N(0,W)\) independently at each step with \[ W \;=\; \mathrm{diag}\!\big(\sigma_x^2,\ \sigma_y^2,\ \sigma_\theta^2\big), \qquad \sigma_x = \sigma_y = 0.01\ \text{m},\quad \sigma_\theta = \mathrm{deg2rad}(0.2). \] This noise perturbs the post-update state components \((p_x,p_y,\theta)\).

Finite-duration “gust” impulse. In addition to \(\eta_t\), we apply a brief deterministic bias over a window \[ t \in [t_g,\ t_g+\Delta] \;=\; [\,4.0\,\mathrm{s},\ 4.8\,\mathrm{s}\,), \] implemented at the discrete indices \(\{t_g,\dots,t_g+\Delta\}\). During this window we set \[ g_t \;=\; \begin{bmatrix} \delta p_x \\[1mm] 0 \\[1mm] \delta \theta \end{bmatrix}, \qquad \delta p_x = 0.01\ \text{m per step},\quad \delta \theta = \mathrm{deg2rad}(1.8)\ \text{per step}, \] and \(g_t=\mathbf{0}\) otherwise. This models a short-lived lateral drift and a heading kick.

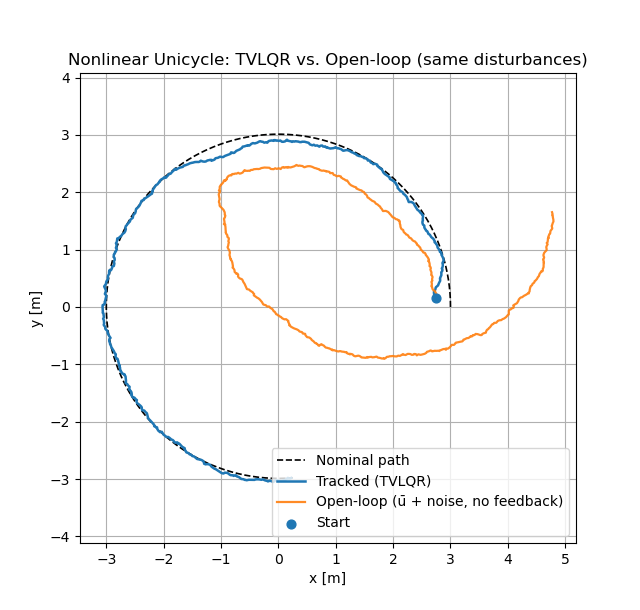

Results. Fig. 4.3 visualizes the nominal trajectory (the dotted circle) and the TVLQR-stabilized trajectory in blue. To clearly see the impact of closed-loop LQR tracking, we also plotted the open-loop trajectory, i.e., the system’s trajectory if no feedback is applied. We can observe that the TVLQR controller effectively rejects the disturbances and stabilizes the closed-loop trajectory along the nominal path.

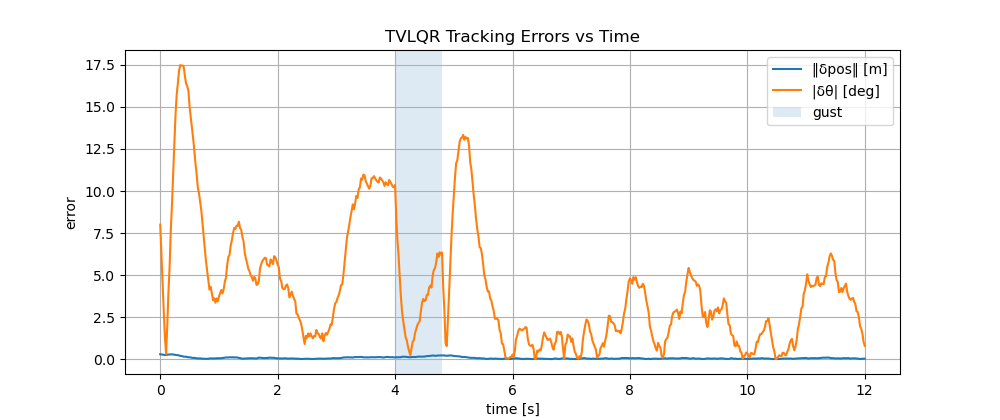

Fig. 4.4 visualizes the state tracking error (position and heading error) as well as compares the closed-loop control with open-loop control.

You can play with the code here.

Figure 4.3: LQR Trajectory Tracking for Unicyle: comparison between nominal trajectory, open-loop trajectory, and closed-loop trajectory with feedback.

Figure 4.4: LQR Trajectory Tracking for Unicyle: state tracking error (top) and control signal (bottom).

4.3 Trajectory Optimization

In Section 4.2 we saw that TVLQR gives a powerful local stabilizer around a nominal state–control sequence \((\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\). This raises a natural question:

Where do nominal trajectories come from?

In many robotics tasks (maneuvering a car, landing a rocket, walking with a robot), we must compute a feasible, high-quality open-loop plan that respects the dynamics and constraints. Trajectory Optimization (TO) does exactly this: it searches over sequences \(\{x_t,u_t\}\) to minimize a cumulative cost while satisfying the system dynamics and constraints.

Moreover, if we can solve TO quickly (or approximately, but reliably), then by re-solving over a short horizon at each time step and applying only the first control, we obtain Model Predictive Control (MPC)—a feedback controller that blends optimization with robustness (see Section 4.4 later). Thus, TO is both a planner and the engine behind feedback via MPC.

General Nonlinear Trajectory Optimization Problem. We adopt the standard discrete-time nonlinear system \[ x_{t+1} = f_t(x_t,u_t),\qquad t=0,\dots,N-1, \] with state \(x_t\in\mathbb{R}^n\) and control \(u_t\in\mathbb{R}^m\). A generic finite-horizon TO problem is \[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \min_{\{x_t,u_t\}} \quad & \Phi(x_N) + \sum_{t=0}^{N-1} \ell_t(x_t,u_t) \\[2mm] \text{s.t.}\quad & x_{t+1} = f_t(x_t,u_t), \qquad t=0,\dots,N-1,\\ & x_0 = \hat x_0 \ \ \text{(given)},\\ & x_t \in \mathcal X_t,\quad u_t \in \mathcal U_t \quad \text{(bounds)},\\ & g_t(x_t,u_t) \le 0,\quad h_t(x_t,u_t)=0 \quad \text{(path/terminal constraints).} \end{split} \tag{4.29} \end{equation}\] Here \(\ell_t\) and \(\Phi\) encode performance (e.g., energy, time, tracking error), \(\mathcal X_t,\mathcal U_t\) capture box limits and safety sets, and \(g_t,h_t\) represent additional nonlinear constraints (obstacles, terminal goals, etc.).

Solving (4.29) directly is difficult in general. A widely used strategy is to iteratively approximate it by quadratic subproblems that can be solved efficiently. This leads to iLQR and its second-order cousin DDP (see Section 4.3.2).

4.3.1 Iterative LQR

High-level intuition. iLQR (iterative LQR) alternates between:

Local modeling: around a current nominal trajectory \(\{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\}\),

- linearize the dynamics,

- quadratically approximate the cost.

- linearize the dynamics,

LQR step: solve the resulting time-varying LQR subproblem to obtain a time-varying affine policy \[ \delta u_t = k_t + K_t\,\delta x_t,\quad \delta x_t:=x_t-\bar x_t,\ \delta u_t:=u_t-\bar u_t, \] which gives both a feedforward step \(k_t\) (to change the nominal control) and a feedback gain \(K_t\) (to stabilize the rollout).

Forward rollout + line search: apply \(u_t^{\text{new}}=\bar u_t+\alpha k_t + K_t(x_t^{\text{new}}-\bar x_t)\) to the true nonlinear dynamics, producing a new nominal trajectory \(\{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\}\). Here we choose \(\alpha\in(0,1]\) to reduce the cost and respect constraints.

Repeat until convergence (cost decrease and dynamics residuals are small).

iLQR can be viewed as a Gauss–Newton method on trajectories: it uses first-order dynamics and second-order cost, capturing the dominant curvature while remaining numerically robust and fast.

4.3.1.1 LQR Subproblem (one iLQR outer iteration)

Given a nominal trajectory \(\{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\}_{t=0}^{N-1}\) with \(\bar x_{t+1}=f_t(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\), define deviations \[ \delta x_t := x_t-\bar x_t,\qquad \delta u_t := u_t-\bar u_t,\qquad \delta x_0\ \text{given.} \]

Linearized Dynamics. We linearize the dynamics along the nominal trajectory \[ \delta x_{t+1} \;\approx\; A_t\,\delta x_t + B_t\,\delta u_t,\quad A_t:=\left.\frac{\partial f_t}{\partial x}\right|_{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)},\ \ B_t:=\left.\frac{\partial f_t}{\partial u}\right|_{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)}. \tag{4.30} \]

Quadratic Cost Approximation. We perform a quadratic approximation of the objective function about \((\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\) \[ \begin{aligned} \ell_t(x_t,u_t) &\approx \ell_t + \ell_{x,t}^\top \delta x_t + \ell_{u,t}^\top \delta u_t + \frac{1}{2} \begin{bmatrix}\delta x_t\\ \delta u_t\end{bmatrix}^{\!\top} \!\begin{bmatrix}\ell_{xx,t} & \ell_{xu,t}\\ \ell_{ux,t} & \ell_{uu,t}\end{bmatrix} \!\begin{bmatrix}\delta x_t\\ \delta u_t\end{bmatrix},\\ \Phi(x_N) &\approx \Phi + \Phi_x^\top \delta x_N + \frac{1}{2}\,\delta x_N^\top \Phi_{xx}\,\delta x_N. \end{aligned} \tag{4.31} \]

The LQR Subproblem. With (4.30)–(4.31), the iLQR subproblem at this outer iteration is the finite-horizon linear–quadratic program in deviations: \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{\{\delta x_t,\delta u_t\}} \quad & \underbrace{\frac{1}{2}\,\delta x_N^\top \Phi_{xx}\,\delta x_N + \Phi_x^\top \delta x_N}_{\text{terminal}} \;+\; \\ & \sum_{t=0}^{N-1} \underbrace{\Big( \frac{1}{2} \begin{bmatrix}\delta x_t\\ \delta u_t\end{bmatrix}^{\!\top} \!\begin{bmatrix}\ell_{xx,t} & \ell_{xu,t}\\ \ell_{ux,t} & \ell_{uu,t}\end{bmatrix} \!\begin{bmatrix}\delta x_t\\ \delta u_t\end{bmatrix} + \ell_{x,t}^\top\delta x_t + \ell_{u,t}^\top\delta u_t \Big)}_{\text{stage}} \\[1mm] \text{s.t.}\quad & \delta x_{t+1} = A_t\,\delta x_t + B_t\,\delta u_t,\qquad t=0,\dots,N-1,\\ & \delta x_0\ \text{given.} \end{aligned} \tag{4.32} \]

Notes. The iLQR subproblem (4.32) is slightly different from the previous finite-horizon LQR formulation (4.3) in the sense that the objective function of (4.32) also contains linear terms in \(\delta x_t,\delta u_t\), and those linear terms come from the Taylor expansion of the original nonlinear objective fuctions. In this case, we will see in the following that the optimal policy is affine (feedforward \(k_t\) + feedback \(K_t\)).

4.3.1.2 Solving the Subproblem by Dynamic Programming

We posit a quadratic value approximator at each time: \[ V_{t}(\delta x_{t}) \;\approx\; V_{t} + V_{x,t}^\top \delta x_t + \frac{1}{2}\,\delta x_t^\top V_{xx,t}\,\delta x_t, \qquad V_{x,N}=\Phi_x,\; V_{xx,N}=\Phi_{xx}. \tag{4.33} \] Note that this quadratic value approximator also contains linear and constant terms because the objective function contains linear terms.

Define the local Q-function at stage \(t\) by substituting the linear dynamics into the next-step value (this is our familiar Q-value in RL): \[ Q_t(\delta x_t,\delta u_t) \;=\; \ell_t(x_t,u_t) + V_{t+1} \big(A_t\delta x_t + B_t\delta u_t\big), \] which, after collecting terms, yields the iLQR blocks \[ \begin{aligned} Q_{x,t}&=\ell_{x,t}+A_t^\top V_{x,t+1},\qquad Q_{u,t}=\ell_{u,t}+B_t^\top V_{x,t+1},\\ Q_{xx,t}&=\ell_{xx,t}+A_t^\top V_{xx,t+1}A_t,\quad Q_{ux,t}=\ell_{ux,t}+B_t^\top V_{xx,t+1}A_t,\\ Q_{uu,t}&=\ell_{uu,t}+B_t^\top V_{xx,t+1}B_t. \end{aligned} \tag{4.34} \] The iLQR blocks assemble into a big matrix such that \[ Q_t(\delta x_t,\delta u_t) \;=\; \frac{1}{2}\, \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ \delta x_t \\ \delta u_t \end{bmatrix}^\top \begin{bmatrix} 2c_t & Q_{x,t}^\top & Q_{u,t}^\top\\[2pt] Q_{x,t} & Q_{xx,t} & Q_{xu,t}\\[2pt] Q_{u,t} & Q_{ux,t} & Q_{uu,t} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ \delta x_t \\ \delta u_t \end{bmatrix}. \tag{4.35} \] where \(c_t\) collects all stage/terminal constants e.g., \(\ell_t+\!V_{t+1}\).

Solving the local Q (backward pass). Set the first-order condition w.r.t. \(\delta u\): \[ 0 \;=\; \partial_{\delta u} Q_t \;=\; Q_{u,t} + Q_{ux,t}\delta x + Q_{uu,t}\delta u. \] Solve for the affine control law \[ \delta u_t^\star \;=\; k_t + K_t\,\delta x,\qquad k_t = -Q_{uu,t}^{-1} Q_{u,t},\quad K_t = -Q_{uu,t}^{-1} Q_{ux,t}\!, \tag{4.36} \] which is exactly the LQR solution for the quadratic \(Q_t\).

Substitute \(\delta u_t^\star\) back into (4.35). The minimized Q becomes a quadratic in \(\delta x\) with coefficients given by \[ \begin{aligned} V_{x,t} &= Q_{x,t} + Q_{xu,t}k_t + K_t^\top Q_{uu,t}k_t + K_t^\top Q_{u,t},\\ V_{xx,t} &= Q_{xx,t} + Q_{xu,t}K_t + K_t^\top Q_{ux,t} + K_t^\top Q_{uu,t}K_t, \end{aligned} \tag{4.37} \] with terminal \[ V_{x,N} = \Phi_x, V_{xx,N} = \Phi_{xx}. \]

Forward Pass (apply the computed policy). Given \(\{k_t,K_t\}\), produce a candidate trajectory on the true nonlinear dynamics using a line search \(\alpha\in(0,1]\): \[ \begin{aligned} u_t^{\text{cand}} &= \bar u_t + \alpha k_t + K_t\big(x_t^{\text{cand}}-\bar x_t\big) ,\\ x_{t+1}^{\text{cand}} &= f_t\big(x_t^{\text{cand}},u_t^{\text{cand}}\big),\qquad x_0^{\text{cand}}=\hat x_0. \end{aligned} \tag{4.38} \] Choose \(\alpha\) (e.g., \(\{1,\frac{1}{2},\frac14,\dots\}\)) to reduce the true cost and respect constraints, then update the nominal: \[ (\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\ \leftarrow\ (x_t^{\text{cand}},u_t^{\text{cand}}). \]

The following pseudocode summarizes iLQR.

Algorithm: iLQR (Trajectory Generation)

Inputs: dynamics \(f_t\), initial state \(\hat x_0\), horizon \(N\), stage/terminal costs \(\ell_t,\Phi\), initial guess \(\{\bar u_t\}\).

- Initialize nominal rollout \(\{\bar x_t,\bar u_t\}\) from \(\hat x_0\).

- Linearize & quadratize at \(\{(\bar x_t,\bar u_t)\}\): build \(A_t,B_t\) and cost derivatives.

- Backward pass (TVLQR): compute \(\{k_t,K_t\}\) using (4.36) and update \(V_{x,t},V_{xx,t}\) via (4.37).

- Forward rollout: apply \(u_t^{\text{new}}=\bar u_t+\alpha k_t+K_t(x_t^{\text{new}}-\bar x_t)\) on the true dynamics, pick \(\alpha\) by line search.

- Convergence check: stop if the cost decrease and dynamics residuals fall below thresholds; otherwise, set the new nominal and repeat from Step 2.

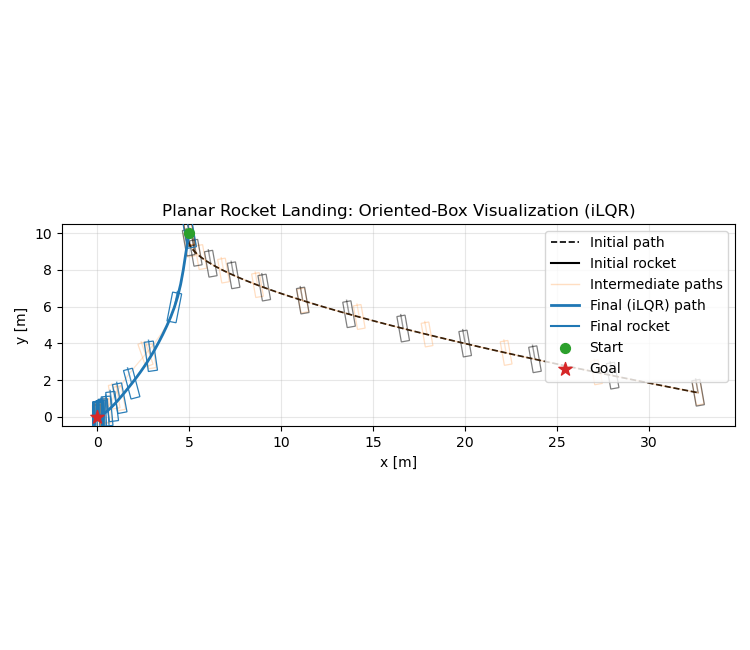

The next example applies iLQR to trajectory generation for rocket landing.

Example 4.3 (iLQR for Rocket Landing) We model a planar (2D) rocket with state and control \[ x=\begin{bmatrix}p_x & p_y & v_x & v_y & \theta & \omega\end{bmatrix}^\top,\qquad u=\begin{bmatrix}T & \tau\end{bmatrix}^\top, \] where \((p_x,p_y)\) is position, \((v_x,v_y)\) is velocity, \(\theta\) is attitude (pitch) and \(\omega\) its angular rate. The thrust \(T\ge 0\) acts along the body axis (pointing out of the engine), and \(\tau\) is a planar torque about the center of mass. Continuous-time dynamics are \[ \begin{aligned} \dot p_x &= v_x, & \dot p_y &= v_y, \\ \dot v_x &= \frac{T}{m}\sin\theta, & \dot v_y &= \frac{T}{m}\cos\theta - g, \\ \dot\theta &= \omega, & \dot\omega &= \frac{\tau}{I_{zz}}. \end{aligned} \tag{4.39} \] In simulation we use RK4 with stepsize \(h\) to propagate the true dynamics (4.39). For iLQR’s local subproblems we form the continuous Jacobians \((A_c,B_c)=\big(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x},\frac{\partial f}{\partial u}\big)\) at the current nominal and use the standard first-order discrete map \[ A_t \;\approx\; I + h\,A_c(\bar x_t,\bar u_t),\qquad B_t \;\approx\; h\,B_c(\bar x_t,\bar u_t). \tag{4.40} \]

Soft-Landing Objective. The goal is a soft, upright landing at the origin: \[ x_{\mathrm{goal}} = \mathbf{0} \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad p_x=p_y=0,\; v_x=v_y=0,\; \theta=0,\; \omega=0. \] We penalize deviations from this goal along the entire trajectory and especially at the terminal state to encourage low touchdown velocities and an upright attitude.

Cost Function. With horizon \(N\) and step \(h\), the discrete objective is \[ J \;=\; \frac{1}{2}\,(x_N-x_g)^\top Q_f (x_N-x_g) \;+\;\sum_{t=0}^{N-1}\Big[ \frac{1}{2}\,(x_t-x_g)^\top Q (x_t-x_g) \;+\; \frac{1}{2}\,u_t^\top R u_t \Big], \tag{4.41} \] where \(x_g=\mathbf{0}\). In the example: \[ \begin{aligned} Q&=\mathrm{diag}(1,\ 2,\ 0.5,\ 0.5,\ 2,\ 0.5),\\ Q_f&=\mathrm{diag}(200,\ 300,\ 50,\ 50,\ 300,\ 50),\\ R&=\mathrm{diag}(10^{-3},\ 10^{-3}). \end{aligned} \tag{4.42} \] These weights place strong emphasis on terminal altitude and attitude (\(p_y,\theta\)), moderate emphasis on velocities and lateral position, and a light regularization on the controls.

Experiment Setup.

Physical parameters. Gravity \(g=9.81\,\mathrm{m/s^2}\), mass \(m=1.0\,\mathrm{kg}\), planar inertia \(I_{zz}=0.2\,\mathrm{kg\,m^2}\).

Discretization. Stepsize \(h=0.05\,\mathrm{s}\); horizon \(T=6.0\,\mathrm{s}\); number of steps \(N=T/h=120\).

Initial state. \[ x_0=\big[\,5.0,\ 10.0,\ -0.5,\ -1.0,\ \mathrm{deg2rad}(10),\ 0\,\big]^\top, \] i.e., 10 m altitude, lateral offset, small descent and slight pitch.

Initial nominal controls. Constant hover thrust and zero torque: \[ \bar u_t = [\,m g,\ 0\,]^\top,\qquad t=0,\dots,N-1. \]

iLQR procedure. Each outer iteration:

- Linearize dynamics and quadratize the cost along the current nominal ((4.40), (4.41));

- Solve the time-varying LQR subproblem to get affine updates \(\delta u_t = k_t + K_t\,\delta x_t\);

- Forward rollout on the nonlinear RK4 dynamics with

\[

u_t^{\text{new}} = \bar u_t + \alpha\,k_t + K_t\big(x_t^{\text{new}}-\bar x_t\big),

\]

using a backtracking line search over \(\alpha\in\{1,\frac{1}{2},\frac14,\dots\}\) (note: \(\alpha\) scales only the feedforward \(k_t\), not the feedback \(K_t\));

- Update the nominal and repeat until cost reduction is small.

- Linearize dynamics and quadratize the cost along the current nominal ((4.40), (4.41));

Fig. 4.5 plots the initial, intermediate, and final trajectories, and render the rocket as oriented rectangles (boxes) using \((p_x,p_y,\theta)\) to visualize attitude along the descent. We can see iLQR successfully generated a soft landing trajectory.

You can play with the code here.

Figure 4.5: iLQR Trajectory Generation for Rocket Landing.

4.3.3 Quadratic Programming

Trajectory optimization (TO) with nonlinear dynamics and objectives is well served by iLQR/DDP: at each outer iteration, they linearize the dynamics and quadratize the objective, then solve a time-varying LQR subproblem. This works remarkably well for unconstrained or softly constrained problems.

However, many TO tasks are constrained—e.g., obstacle avoidance, actuator limits, keep-out zones, terminal envelopes. Hard constraints are awkward for iLQR/DDP (they typically enter via penalties or saturations), and feasibility can be fragile. For such cases, it is often more natural to frame TO as a nonlinear program (NLP)—an optimization problem with general nonlinear objective and constraints. This brings the full machinery of modern numerical optimization (see, e.g., (Nocedal and Wright 1999)).

As a first step, we study the convex special case where the linearization already yields linear dynamics, affine constraints, and a quadratic objective (these are typically known as “constrained LQR” problems). This leads to Quadratic Programming (QP), a cornerstone problem class with mature, efficient solvers. In the next section, we will lift these ideas to Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) to handle general constrained TO.

4.3.3.1 From Trajectory Optimization to Quadratic Programming

Start from the constrained TO template in (4.29). Suppose:

- Linear (time-varying) dynamics (from linearization or an intrinsically linear model): \[ x_{t+1} = A_t x_t + B_t u_t + a_t,\qquad t=0,\dots,N-1, \] with given \(x_0=\hat x_0\).

- Quadratic objective (from quadratization or an Linear-Quadratic tracking design): \[ \Phi(x_N) + \sum_{t=0}^{N-1} \ell_t(x_t,u_t) \;\equiv\; \frac{1}{2}\,x_N^\top Q_N x_N + q_N^\top x_N + \sum_{t=0}^{N-1}\Big(\frac{1}{2}\,[x_t;u_t]^\top H_t [x_t;u_t] + h_t^\top [x_t;u_t]\Big), \] with \(Q_N\succeq 0\), \(H_t=\begin{bmatrix}Q_t & S_t\\ S_t^\top & R_t\end{bmatrix} \succeq 0\) and \(R_t\succ 0\) for convexity.

- Affine path/terminal constraints (from linearized safety/goal constraints): \[ G_t^x x_t + G_t^u u_t \le g_t,\qquad F_x x_N \leq f. \]

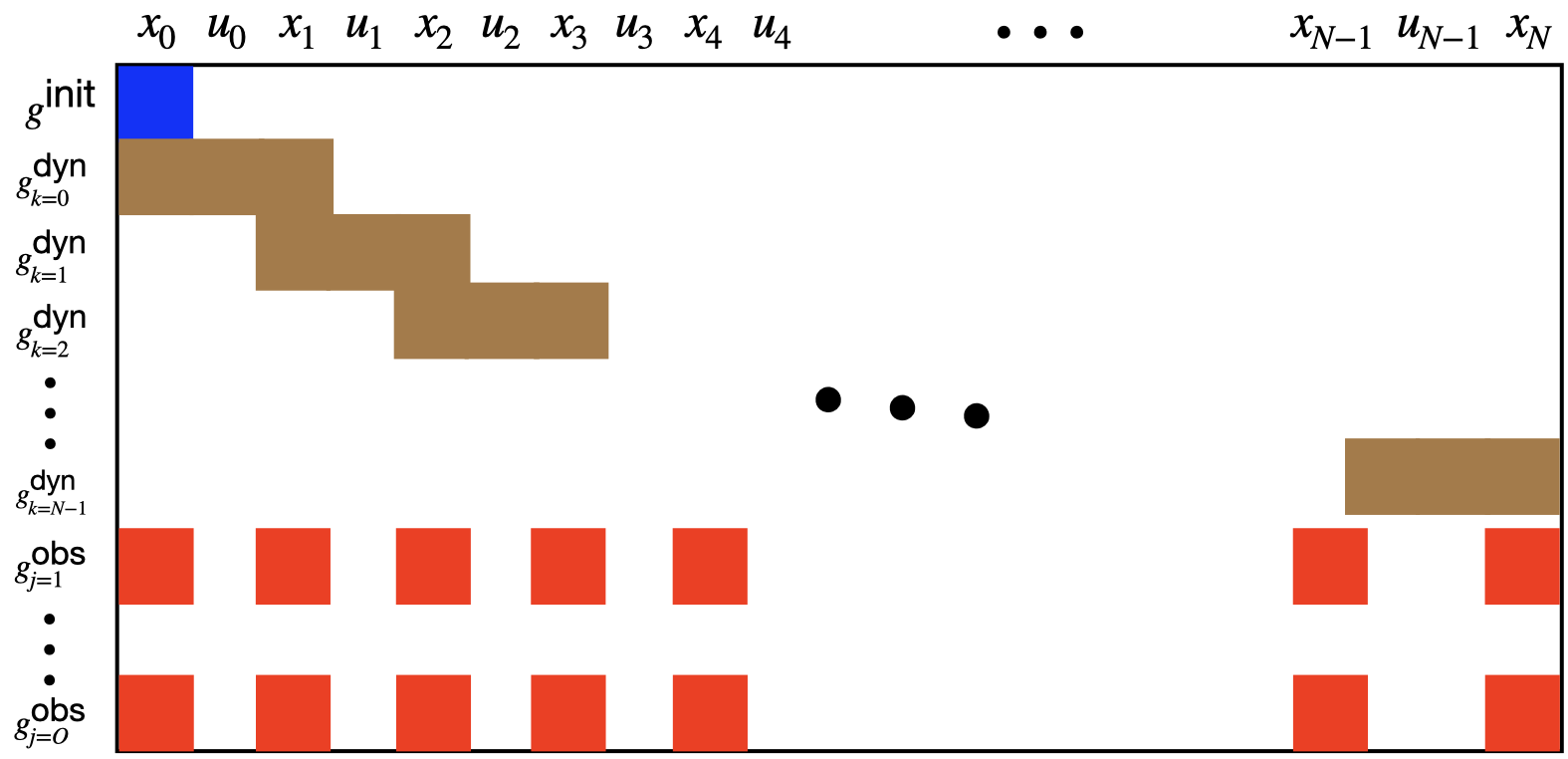

Define the stacked decision vector \[ z := \big[x_0^\top,\,u_0^\top,\,x_1^\top,\,u_1^\top,\,\dots,\,x_{N-1}^\top,\,u_{N-1}^\top,\,x_N^\top\big]^\top. \] Then the horizon-wide problem is a QP: \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{z}\quad & \frac{1}{2}\, z^\top H\, z \;+\; h^\top z \\[2mm] \text{s.t.}\quad & A_{\text{dyn}}\, z = b_{\text{dyn}} \quad \text{(stacked dynamics and } x_0=\hat x_0\text{)},\\ & G\, z \le g \qquad\quad\ \ \text{(stacked affine path/terminal constraints)}\\ \end{aligned} \tag{4.43} \] Here \(H\succeq 0\) is block-sparse (banded) due to the stagewise structure; the constraint matrices are also sparse/banded because each dynamic constraint couples only \((x_t,u_t,x_{t+1})\).

Exercise 4.1 Can you write down the blocks in \(H\), \(A\), and \(G\), as functions of \(H_t,A_t,B_t,G^x_t, G^u_t\)? Then, observe the block-sparsity patterns.

Convexity. If all stage Hessians \(H_t\succeq 0\) and \(Q_N\succeq 0\), (4.43) is a convex QP with a unique minimizer when \(H\) is positive definite on the feasible subspace (e.g., via \(R_t\succ 0\)).

4.3.3.2 Solving the Quadratic Program

We now discuss how to solve a general convex quadratic program (QP) containing both equality and inequality constraints: \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{z \in \mathbb{R}^n}\quad & \frac{1}{2}\, z^\top H\, z \;+\; h^\top z \\ \text{s.t.}\quad & A z = b \\ & G z \le g \end{aligned} \tag{4.44} \] where \(z \in \mathbb{R}^n\) is the decision variable, \(H \in \mathbb{S}^{n}, h \in \mathbb{R}^n, A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}, b \in \mathbb{R}^m, G \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times n}, g \in \mathbb{R}^p\) are given problem data (e.g., generated as in Section 4.3.3.1). We assume \(H \succeq 0\) is positive semidefinite.

There are multiple popular algorithms to solve (4.44), e.g., the active set algorithm, the interior point algorithm, and the alternating direction method of multipliers. Here we only present the primal–dual interior point method (PD-IPM) due to its generality and robustness. Before presenting the PD-IPM algorithm, it is beneficial to review Newton’s method for solving a system of equations.

Newton’s Method

Given a function \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) that is continuously differentiable, Newton’s method is designed to find a root of \[ f(x) = 0. \] Given an initial iterate \(x^{(0)}\), Newton’s method works as follows \[ x^{(k+1)} = x^{(k)} - \frac{f(x^{(k)})}{f'(x^{(k)})}, \] where \(f'(x^{(k)})\) denotes the derivative of \(f\) at the current iterate \(x^{(k)}\). This simple algorithm is indeed the most important foundation of modern numerical optimization. Under mild conditions, Newton’s method has at least quadratic convergence rate, that is to say, if \(|x^{(k)} - x^\star| = \epsilon\), then \(|x^{(k+1)} - x^\star| = O(\epsilon^2)\) (it should be noted that there exist pathological cases where even linear convergence is not guaranteed, e.g., when \(f'(x^\star) = 0\)).

Newton’s method can be generalized to find a point at which multiple functions vanish simultaneously. Given a function \(F: \mathbb{R}^{n} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{n}\) that is continuously differentiable, and an initial iterate \(x^{(0)}\), Newton’s method reads \[\begin{equation} x^{(k+1)} = x^{(k)} - J_F(x^{(k)})^{-1} F(x^{(k)}), \tag{4.45} \end{equation}\] where \(J_F(\cdot)\) denotes the Jacobian of \(F\). Iteration (4.45) is equivalent to \[\begin{equation} \begin{split} J_F(x^{(k)}) \Delta x^{(k)} & = - F(x^{(k)}) \\ x^{(k+1)} & = x^{(k)} + \Delta x^{(k)} \end{split} \tag{4.46} \end{equation}\] i.e., one first solves a linear system of equations to find an update direction \(\Delta x^{(k)}\), and then take a step along the direction.

As we will see, PD-IPMs for solving convex QPs can be seen as applying Newton’s method to the perturbed KKT system of optimality conditions.

Slacks, Lagrangian, and KKT Optimality. Introduce \(s\in\mathbb{R}^p\) so that \[ Gz + s = g,\qquad s \ge 0. \tag{4.47} \] Let \(y\in\mathbb{R}^m\) be the Lagrangian multipliers for \(Az=b\), \(\nu\in\mathbb{R}^p\) for the equality \(Gz+s=g\), and \(w\in\mathbb{R}^p\) (with \(w\ge 0\)) for the inequality \(s\ge 0\). The Lagrangian for the QP (4.44) is \[ \mathcal L(z,s,y,\nu,w) = \frac{1}{2} z^\top H z + h^\top z + y^\top(Az-b) + \nu^\top(Gz+s-g) - w^\top s. \tag{4.48} \] From the Lagrangian, we can derive the KKT optimality conditions, i.e., under technical conditions (such as constraint qualification), a point \((z,s)\) is a local minimizer of the QP if and only if there exists dual variables \((\nu,w)\) satisfying: \[ \begin{aligned} \text{(stationarity)}&:\quad \nabla_z\mathcal L = H z + h + A^\top y + G^\top \nu = 0,\\ &\quad \nabla_s\mathcal L = \nu - w = 0 \ \Longrightarrow\ \nu = w,\\[2pt] \text{(primal feasibility)}&:\quad A z - b = 0,\qquad G z + s - g = 0, \qquad s \ge 0, \\ \text{(dual feasibility)}&:\quad w \ge 0,\\ \text{(complementarity)}&:\quad s_i w_i = 0,\quad i=1,\dots,p. \end{aligned} \tag{4.49} \] Using \(\nu=w\) we eliminate \(\nu\) and keep variables \((z,s,y,w)\). Since the QP is convex, we know that any local minimizer is a global minimizer. Hence, if we can solve the KKT system (4.49), we can find an optimal solution of the QP.

If you are not familiar with the Lagrangian and the KKT optimality conditions, make sure to review Appendix A.1.3 and A.1.4.

Central Path and Residuals. Replace complementarity by the perturbed condition \[ S W \mathbf{1} = \sigma \mu\,\mathbf{1}, \qquad \mu := \frac{1}{p}\, s^\top w, \qquad \sigma \in (0,1) \tag{4.50} \] with \(S=\mathrm{diag}(s)\), \(W=\mathrm{diag}(w)\). At a current iterate \((z,s,y,w)\) define residuals \[ \begin{aligned} r_{\mathrm{dual}} &= H z + h + A^\top y + G^\top w,\\ r_{\mathrm{pe}} &= A z - b,\\ r_{\mathrm{pi}} &= G z + s - g,\\ r_{\mathrm{cent}} &= S W \mathbf{1} - \sigma \mu\,\mathbf{1}. \end{aligned} \tag{4.51} \]

Newton System (primal–dual step). Now that we have arrived at the perturbed KKT system of equations in (4.51) where we aim to drive all the residuals to zero. This is a system of \((n+m+p+p)\) nonlinear equations in \((n + m + p + p)\) variables. Therefore, we can apply Newton’s method to solve the system of equations.

Note that we actually want to solve the original KKT system with \(\sigma \mu = 0\). However, this system is ill-conditioned and directly applying Newton’s method would lead to instability. Therefore, we solve the perturbed KKT system with \(\sigma \mu > 0\) and at each iteration we move closer to the original KKT system with \(\sigma \in (0,1)\) so that in the limit we will converge (arbitrarily close) to a solution of the original KKT system.

Solve for the Newton direction \((\Delta z,\Delta s,\Delta y,\Delta w)\): \[ \begin{aligned} H\,\Delta z + A^\top \Delta y + G^\top \Delta w &= -\,r_{\mathrm{dual}},\\ A\,\Delta z &= -\,r_{\mathrm{pe}},\\ G\,\Delta z + \Delta s &= -\,r_{\mathrm{pi}},\\ W\,\Delta s + S\,\Delta w &= -\,r_{\mathrm{cent}}. \end{aligned} \tag{4.52} \] Eliminate \(\Delta s = -r_{\mathrm{pi}} - G\Delta z\) in the last equation to get \[ S\,\Delta w = -\,r_{\mathrm{cent}} + W\,r_{\mathrm{pi}} + W\,G\,\Delta z \quad\Longrightarrow\quad \Delta w = S^{-1}\!\left(-r_{\mathrm{cent}} + W r_{\mathrm{pi}} + W G \Delta z\right). \] Substitute into the first equation to obtain the reduced symmetric system in \((\Delta z,\Delta y)\): \[ \begin{bmatrix} H + G^\top D G & A^\top\\ A & \ \ 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}\Delta z\\ \Delta y\end{bmatrix} = - \begin{bmatrix} r_{\mathrm{dual}} - G^\top S^{-1} \big(r_{\mathrm{cent}} + W r_{\mathrm{pi}}\big)\\[2pt] r_{\mathrm{pe}} \end{bmatrix} \tag{4.53} \] with \(D := S^{-1} W\). Then recover \[ \Delta w = S^{-1}\!\left(-r_{\mathrm{cent}} + W r_{\mathrm{pi}} + W G \Delta z\right),\qquad \Delta s = -r_{\mathrm{pi}} - G \Delta z. \]

Step Lengths. Choose step sizes to preserve positivity of \(s,w\): \[ \alpha_{\mathrm{pri}} = \min\!\Big(1,\ \eta \min_{\Delta s_i<0}\frac{-s_i}{\Delta s_i}\Big),\qquad \alpha_{\mathrm{du}} = \min\!\Big(1,\ \eta \min_{\Delta w_i<0}\frac{-w_i}{\Delta w_i}\Big), \tag{4.54} \] with \(\eta\in(0,1)\) (e.g., \(0.99\)). Update both primal and dual variables \[ \begin{aligned} z &\leftarrow z + \alpha_{\mathrm{pri}}\,\Delta z,\qquad s \leftarrow s + \alpha_{\mathrm{pri}}\,\Delta s,\\ y &\leftarrow y + \alpha_{\mathrm{du}}\,\Delta y,\qquad w \leftarrow w + \alpha_{\mathrm{du}}\,\Delta w. \end{aligned} \]

Initialization and Stopping.

- Initialization. Find any \(z\) satisfying \(Az=b\) (e.g., least-squares projection). Set \[ s := \max\{\mathbf{1},\, g - Gz\},\quad w := \mathbf{1}, \] to ensure strict positivity (\(s>0,w>0\)); choose \(y:=0\).

- Stopping. Terminate when \[ \|r_{\mathrm{dual}}\|_\infty \le \varepsilon,\quad \|r_{\mathrm{pe}}\|_\infty \le \varepsilon,\quad \|r_{\mathrm{pi}}\|_\infty \le \varepsilon,\quad \mu \le \varepsilon, \] for a small tolerance \(\varepsilon\) (e.g., \(10^{-6}\)).

The following pseudocode implements the PD-IPM algorithm for solving convex QP.

Algorithm: Primal–Dual Interior-Point for Convex QP

Input: \(H\succeq 0, h, A,b, G,g\); tolerance \(\varepsilon\); \(\eta=0.99\); \(\sigma \in (0,1)\)

- Initialize \(z\) with \(Az=b\); set \(s>0, w>0\) (e.g., \(s=\max\{1,g-Gz\}\), \(w=\mathbf{1}\)); set \(y=0\).

- Repeat until convergence:

- Compute residuals \(r_{\mathrm{dual}}, r_{\mathrm{pe}}, r_{\mathrm{pi}}\), \(\mu=(s^\top w)/p\).

- Solve the reduced system (4.53) to obtain Newton direction.

- Compute \(\alpha_{\mathrm{pri}},\alpha_{\mathrm{du}}\) by (4.54).

- Update \((z,s,y,w)\).

- Check stopping criteria; if satisfied, return \(z^\star\).

Remarks.

For QPs obtained from trajectory optimization problems, the matrices are typically sparse (e.g., time-banded sparsity). This sparsity can be leveraged when forming and solving the Newton direction.

In practice, Mehrotra’s predictor–corrector method is used to improve the robustness and convergence of PD-IPM.

Software. It is important to understand the high-level algorithmic idea for solving a convex QP. However, in practice, there are many mature QP solvers and it takes just a few lines of code to call your favorite QP solver.

The following code snippet shows how to define a QP in cvxpy and then solve it using MOSEK (which implements PD-IPM).

# Minimal dense QP with CVXPY

# minimize (1/2) x^T P x + q^T x

# subject to Ax <= b, 1^T x = 1

#

# pip install cvxpy

import numpy as np

import cvxpy as cp

# ----- QP data (dense) -----

P = np.array([

[4.0, 1.0, 0.5],

[1.0, 2.0, 0.3],

[0.5, 0.3, 1.5]

], dtype=float)

# Make sure P is symmetric positive definite

P = 0.5 * (P + P.T) + 1e-9 * np.eye(3)

q = np.array([-1.0, -2.0, -3.0])

A = np.array([

[1.0, -2.0, 1.0], # linear inequality: x1 - 2 x2 + x3 ≤ 2

[-1.0, 0.0, 0.0], # x1 ≥ 0 -> -x1 ≤ 0

[0.0, -1.0, 0.0], # x2 ≥ 0 -> -x2 ≤ 0

[0.0, 0.0, -1.0], # x3 ≥ 0 -> -x3 ≤ 0

[1.0, 0.0, 0.0], # x1 ≤ 1.5

[0.0, 1.0, 0.0], # x2 ≤ 1.5

[0.0, 0.0, 1.0], # x3 ≤ 1.5

])

b = np.array([2.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.5, 1.5, 1.5])

# Equality: sum(x) = 1

e = np.ones((1, 3))

d = np.array([1.0])

# ----- CVXPY problem -----

x = cp.Variable(3)

objective = cp.Minimize(0.5 * cp.quad_form(x, P) + q @ x)

constraints = [

A @ x <= b,

e @ x == d

]

prob = cp.Problem(objective, constraints)

# You can choose a solver; OSQP is common for QPs. ECOS/SCS also work.

prob.solve(solver=cp.MOSEK, verbose=True)

print("Status:", prob.status)

print("Optimal value:", prob.value)

print("x* =", x.value.round(6))

# (Optional) check constraints

ineq_res = (A @ x.value - b)

eq_res = (e @ x.value - d)

print("Max inequality residual (<=0):", np.max(ineq_res))

print("Equality residual (≈0):", eq_res.item())Running the code produces the following output. You should now be able to interpret the iterations of MOSEK.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Numerical solver

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:51 PM: Invoking solver MOSEK to obtain a solution.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Problem

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Name :

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Objective sense : maximize

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Type : CONIC (conic optimization problem)

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Constraints : 4

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Affine conic cons. : 0

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Disjunctive cons. : 0

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Cones : 1

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Scalar variables : 13

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Matrix variables : 0

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Integer variables : 0

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM:

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimizer started.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Presolve started.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Linear dependency checker started.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Linear dependency checker terminated.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Eliminator started.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Freed constraints in eliminator : 1

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Eliminator terminated.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Eliminator started.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Freed constraints in eliminator : 0

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Eliminator terminated.

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Eliminator - tries : 2 time : 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Lin. dep. - tries : 1 time : 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Lin. dep. - primal attempts : 1 successes : 1

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Lin. dep. - dual attempts : 0 successes : 0

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Lin. dep. - primal deps. : 0 dual deps. : 0

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Presolve terminated. Time: 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimizer - threads : 12

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimizer - solved problem : the primal

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimizer - Constraints : 3

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimizer - Cones : 1

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimizer - Scalar variables : 10 conic : 5

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimizer - Semi-definite variables: 0 scalarized : 0

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Factor - setup time : 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Factor - dense det. time : 0.00 GP order time : 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Factor - nonzeros before factor : 6 after factor : 6

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Factor - dense dim. : 0 flops : 6.40e+01

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: ITE PFEAS DFEAS GFEAS PRSTATUS POBJ DOBJ MU TIME

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 0 1.3e+00 3.0e+00 2.0e+00 0.00e+00 -2.000000000e+00 -1.000000000e+00 1.0e+00 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 1 2.2e-01 5.3e-01 2.4e-01 1.05e-01 -1.810182709e+00 -1.723136430e+00 1.8e-01 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 2 3.7e-02 8.9e-02 1.6e-02 9.48e-01 -2.154687486e+00 -2.135415569e+00 3.0e-02 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 3 1.0e-02 2.5e-02 2.2e-03 1.01e+00 -2.236775806e+00 -2.230836084e+00 8.2e-03 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 4 2.8e-03 6.7e-03 3.2e-04 1.02e+00 -2.250313751e+00 -2.248643381e+00 2.2e-03 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 5 7.7e-04 1.8e-03 4.5e-05 1.00e+00 -2.256166317e+00 -2.255708191e+00 6.1e-04 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 6 2.1e-05 5.1e-05 2.1e-07 1.00e+00 -2.256863865e+00 -2.256850955e+00 1.7e-05 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 7 1.0e-07 2.4e-07 6.8e-11 1.00e+00 -2.256896295e+00 -2.256896233e+00 8.1e-08 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: 8 8.5e-09 2.0e-08 1.6e-12 1.00e+00 -2.256896526e+00 -2.256896521e+00 6.7e-09 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimizer terminated. Time: 0.00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM:

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM:

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Interior-point solution summary

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Problem status : PRIMAL_AND_DUAL_FEASIBLE

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Solution status : OPTIMAL

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Primal. obj: -2.2568965259e+00 nrm: 3e+00 Viol. con: 2e-08 var: 1e-08 cones: 0e+00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Dual. obj: -2.2568965208e+00 nrm: 1e+00 Viol. con: 0e+00 var: 2e-08 cones: 0e+00

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Summary

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Problem status: optimal

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Optimal value: -2.257e+00

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Compilation took 3.196e-03 seconds

(CVXPY) Nov 04 12:06:52 PM: Solver (including time spent in interface) took 1.100e+00 seconds

Status: optimal

Optimal value: -2.256896525744356

x* = [0. 0.068914 0.931086]

Max inequality residual (<=0): -1.938693250380652e-08

Equality residual (≈0): 0.04.3.4 Sequential Quadratic Programming

We have seen that quadratic programs (QPs) gracefully handle constrained LQR–style trajectory optimization: convex quadratic costs, linear dynamics, and affine path/terminal constraints. With time-stacked sparsity, these problems are solved efficiently (e.g., via interior-point methods), making QP a strong tool for that regime.

The natural next step is the general trajectory optimization problem in (4.29), which features nonlinear dynamics, nonconvex objectives, and nonlinear constraints. To tackle this, we turn to Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP)—a Newton-like framework that iteratively linearizes the dynamics/constraints and quadratizes the objective to form a sequence of QP subproblems. Each QP is solved to produce a step and updated multipliers; with globalization and appropriate Hessian modeling, the sequence converges to a locally optimal solution (a KKT point) of the original nonlinear TO problem. In short: QP handles the convex linearized case; SQP extends that logic to the full nonlinear setting by repeatedly building and solving the right QP at the current iterate. For an in-depth presentation of SQP for nonlinear programming, we refer to Chapter 18 of (Nocedal and Wright 1999).

4.3.4.1 Problem Statement

We will consider the following general nonlinear program (NLP) \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{x\in\mathbb{R}^n}\quad & f(x) \\ \text{s.t.}\quad & c(x)=0 \quad (c:\mathbb{R}^n\!\to\mathbb{R}^{m}),\\ & d(x)\le 0 \quad (d:\mathbb{R}^n\!\to\mathbb{R}^{p}), \end{aligned} \tag{4.55} \] with objective function \(f(x)\), equality constraints \(c(x)=0\), and inequality constraints \(d(x)\leq 0\). To obtain the NLP formulation (4.55) from the TO template (4.29), one needs to define the set constraints \(x_t \in \mathcal{X}_t\) and \(u_t \in \mathcal{U}_t\) as general equality and inequality constraints. The decision variable \(x\) contains the entire sequence of states and actions.

While in many cases the functions \(f,c,d\) are defined analytically, technically speaking, we only need zero-order and first-order oracles of these functions to implement numerical algorithms. That is, given a point \(x\), we need to evaluate \(f(x), c(x), d(x)\) and their first-order derivatives.

With dual variables \(\lambda \in \mathbb{R}^m\) and \(\mu \in \mathbb{R}^p\), define the Lagrangian of (4.55) as \[ \mathcal L(x,\lambda,\mu) \;=\; f(x) + \lambda^\top c(x) + \mu^\top d(x),\qquad \mu\ge 0, \] and Jacobians \(J_c(x):=\nabla c(x)\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times n}\), \(J_d(x):=\nabla d(x)\in\mathbb{R}^{p\times n}\).

4.3.4.2 High-Level Intuition

At a current iterate \(x_k\), we (1) Linearize the constraints and (2) quadratize the Lagrangian to build a local QP. Solving this QP yields a primal step \(p_k\) and updated multipliers \((\lambda_{k+1},\mu_{k+1})\) (from QP duals). A line-search (or trust-region) with a merit or filter globalization ensures convergence from remote starts.

Key ingredients:

A Hessian (or quasi-Newton) approximation \(H_k \approx \nabla_{xx}^2\mathcal L(x_k,\lambda_k,\mu_k)\).

A QP subproblem capturing first-order feasibility and second-order optimality locally.

A globalization mechanism (\(\ell_1\) merit or filter) + optional second-order correction (SOC) to mitigate linearization error in active inequalities.

4.3.4.3 The SQP QP Subproblem

Given the current iterate \((x_k,\lambda_k,\mu_k)\), define \[ g_k := \nabla f(x_k),\qquad c_k := c(x_k),\qquad d_k := d(x_k),\qquad A_k := J_c(x_k),\qquad G_k := J_d(x_k). \] Let \(H_k\) be a symmetric approximation to \(\nabla_{xx}^2 \mathcal L(x_k,\lambda_k,\mu_k)\) (see Section 4.3.4.4).

The QP subproblem in this step is \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{p\in\mathbb{R}^n}\quad & \frac{1}{2} p^\top H_k\, p + g_k^\top p \\[1mm] \text{s.t.}\quad & A_k\, p + c_k = 0, \\ & G_k\, p + d_k \le 0. \end{aligned} \tag{4.56} \] This defines a local quadratic model of (4.55): constraints are linearized; the objective is the second-order Taylor model of the Lagrangian (up to a constant).

Solving the QP subproblem (4.56) returns:

- Primal step \(p_k\).

- Dual estimates \(\lambda_{k+1}^{\text{QP}}, \mu_{k+1}^{\text{QP}}\) (the QP multipliers), which we use as new multipliers.

4.3.4.4 Hessian Approximation

The most natural choice for \(H_k\) in the QP subproblem (4.56) is the exact Hessian: \[ H_k = \nabla_{xx}^2 \mathcal{L}(x_k, \lambda_k, \mu_k) = \nabla_{xx}^2 f(x_k) + \sum_{i} \lambda_{k,i} \nabla_{xx}^2 c_i(x_k) + \sum_{i} \mu_{k,i} \nabla_{xx}^2 d_i(x_k). \] However, two potential issues with the exact Hessian are (i) it can be costly to build and store the analytic Hessians \(\nabla_{xx}^2 f, \nabla_{xx}^2 c_i, \nabla_{xx}^2 d_i\); (ii) the exact Hessian \(H_k\) may not be positive semidefinite, which may lead to failure of convexity in the QP subproblem.

A cornerstone result in numerical optimization, due to Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS), is to build an approximate Hessian from first-order derivatives. In particular, given two consecutive primal iterates \(x_{k+1}, x_k\) (and their associated dual variables) and first-order gradients of the Lagrangian \(\nabla_x \mathcal{L}(x_{k+1}, \lambda_{k+1}, \mu_{k+1})\), \(\nabla_x \mathcal{L}(x_{k}, \lambda_{k}, \mu_{k})\), define \[ s_k := x_{k+1}-x_k,\qquad y_k := \nabla_x \mathcal L(x_{k+1},\lambda_{k+1},\mu_{k+1}) - \nabla_x \mathcal L(x_k,\lambda_k,\mu_k). \] The BFGS quasi-Newton method updates \(H_{k+1}\) from \(H_k\) as follows \[ H_{k+1} = H_k - \frac{H_k s_k s_k^\top H_k}{s_k^\top H_k s_k} + \frac{y_k y_k^\top}{s_k^\top y_k}. \tag{4.57} \] One can show that if \(y_k^\top s_k > 0\) holds, the BFGS Hessian approximation is always positive definite (provided \(H_0 \succ 0\)). Therefore, the BFGS Hessian approximation ensures the QP subproblem is convex. If the curvature condition \(y_k^\top s_k > 0\) fails to hold, one can resort to damped BFGS, see (Nocedal and Wright 1999).

There is a broad family of quasi-Newton methods with BFGS being one of the most popular instances. For example, the symmetric rank-one (SR1) method is another popular quasi-Newton variant. In addition, the “limited memory” version of quasi-Newton methods (e.g., limited memory BFGS (Liu and Nocedal 1989)) can further reduce the price of Hessian approximation by only looking at the history of a small amount of gradients.

4.3.4.5 Globalization: Merit or Filter

To accept a step, we assess optimality improvement + feasibility improvement:

\(\ell_1\) merit (exact-penalty style): define the merit function \[ \phi_\rho(x) = f(x) + \rho \big(\|c(x)\|_1 + \|d^+(x)\|_1\big),\quad d^+ := \max(d,0), \] with penalty \(\rho\) large enough (\(\rho\) can also be adaptive with respect to iterations). Use backtracking line search on \(\phi_\rho(x_k+\alpha p_k)\) to ensure decrease of the merit function.

Filter method: Maintain a set of pairs \((\text{feasibility},\text{objective})\). Accept steps that reduce either feasibility or objective sufficiently without worsening the other beyond the filter. Often paired with Second-order correction, see more details in (Nocedal and Wright 1999).

The following pseudocode implements a basic line-search SQP with quasi-Newton Hessian approximation.

Algorithm: Line-Search SQP

Inputs: \(x_0\), multipliers \((\lambda_0,\mu_0\ge 0)\), initial Hessian \(H_0\succ 0\) (e.g., \(\gamma I\)), globalization parameters.

For \(k=0,1,2,\dots\)

Linearize & build QP: form \(g_k, A_k, G_k, c_k, d_k\) and \(H_k\), then solve the QP (4.56) to get \(p_k\) and QP multipliers \((\hat\lambda_{k+1},\hat\mu_{k+1}\ge 0)\).

Globalization: Choose step size \(\alpha_k\in(0,1]\) by backtracking on the \(\ell_1\)-merit.

Update: \[ x_{k+1} = x_k + \alpha_k p_k,\qquad \lambda_{k+1} = \hat\lambda_{k+1},\qquad \mu_{k+1} = \Pi_{\ge 0}(\hat\mu_{k+1}). \]

Hessian (quasi-Newton) update: define \[ s_k := x_{k+1}-x_k,\qquad y_k := \nabla_x \mathcal L(x_{k+1},\lambda_{k+1},\mu_{k+1}) - \nabla_x \mathcal L(x_k,\lambda_k,\mu_k). \] update \[ H_{k+1} = H_k - \frac{H_k s_k s_k^\top H_k}{s_k^\top H_k s_k} + \frac{y_k y_k^\top}{s_k^\top y_k}. \]

Stopping: if KKT residuals (stationarity, primal feasibility, complementarity) are below tolerance, terminate.

Notes.

Trust-region SQP. An alternative globalization: add \(\|p\|\le \Delta\) or a quadratic trust region, and update \(\Delta\) by comparing predicted vs. actual reduction in a composite model.

Software. The

scipypackage in Python implements SLSQP, which is basically the line-search SQP we presented above. A more advanced version of SQP is provided by the SNOPT commercial software. The CRISP software provides a C++ implementation of an SQP algorithm. Additionally, Matlab’sfminconprovides an implementation of SQP.

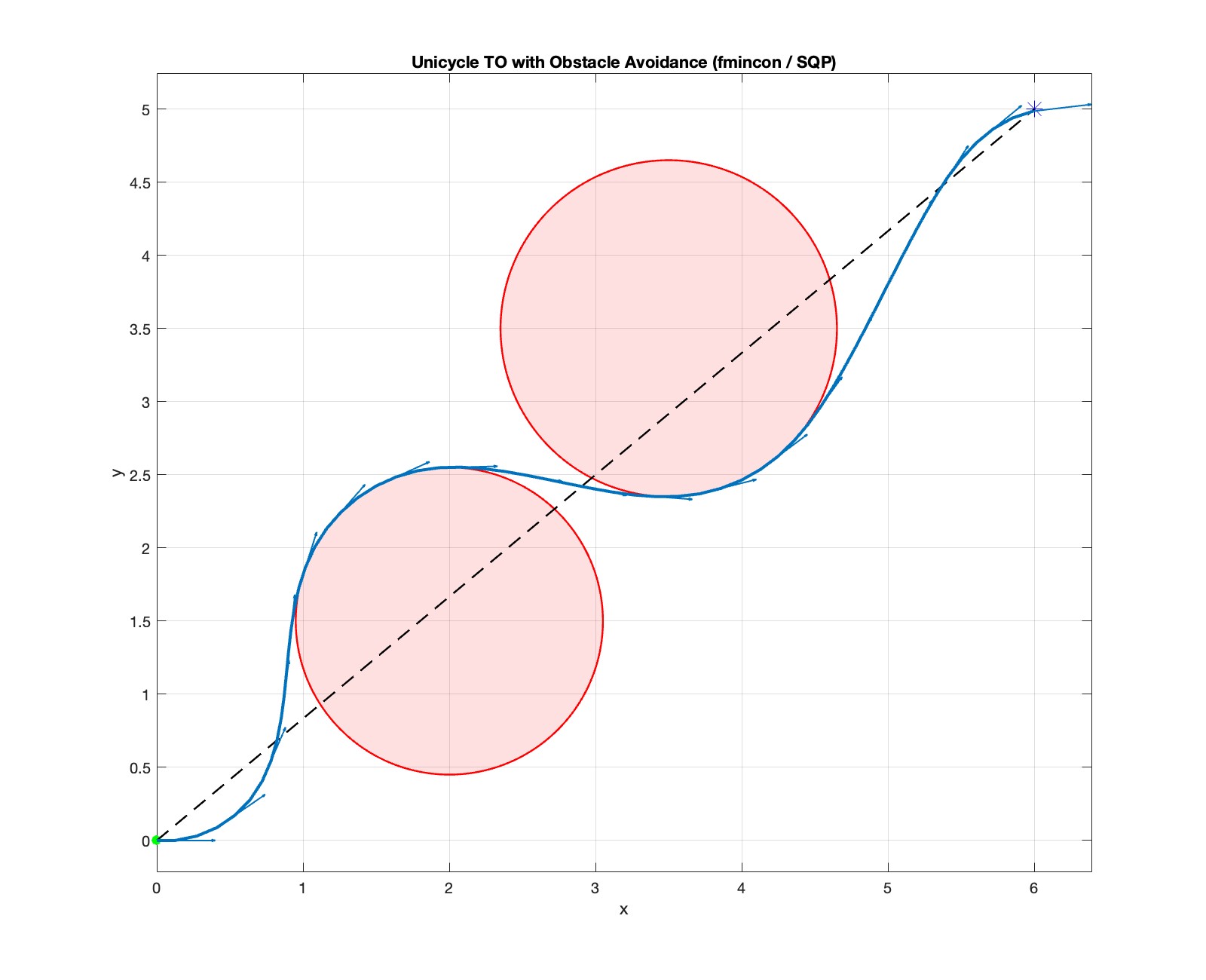

Example 4.4 (Trajectory Optimization with SQP) We formulate a trajectory optimization (TO) problem for a unicycle robot that must travel from a start pose \(A\) to a goal pose \(B\) while avoiding circular (ball-shaped) obstacles.

System Model. We use the standard unicycle (Dubins-like) kinematics in continuous time: \[ \dot{x}(t)= \begin{bmatrix} \dot{p}_x\\[2pt]\dot{p}_y\\[2pt]\dot{\theta} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} v(t)\cos\theta(t)\\ v(t)\sin\theta(t)\\ \omega(t) \end{bmatrix}, \qquad x=[p_x,p_y,\theta]^\top,\ \ u=[v,\omega]^\top. \tag{4.58} \]

We discretize on a uniform grid \(t_k=k h,\ k=0,\dots,N\) with step \(h>0\) by forward Euler: \[ x_{k+1} \;=\; f_h(x_k,u_k) \;:=\; \begin{bmatrix} p_{x,k} + h\, v_k \cos \theta_k\\ p_{y,k} + h\, v_k \sin \theta_k\\ \theta_k + h\, \omega_k \end{bmatrix}. \tag{4.59} \]

Decision Variables. We optimize over the state–control sequence \[ \{x_k\}_{k=0}^N,\quad \{u_k\}_{k=0}^{N-1}, \] and collect them into a single vector \[ z = \big[x_0^\top,\ u_0^\top,\ x_1^\top,\ u_1^\top,\ \dots,\ x_{N-1}^\top,\ u_{N-1}^\top,\ x_N^\top\big]^\top \;\in\;\mathbb{R}^{(3+2)N+3}. \tag{4.60} \]

Constraints. We impose the following constraints.

(i) Initial condition. \[ x_0 = A \in \mathbb{R}^3. \tag{4.61} \]

(ii) System dynamics (equality constraints). For \(k=0,\dots,N-1\), \[ x_{k+1} - f_h(x_k,u_k) = 0. \tag{4.62} \]

(iii) Obstacle avoidance (inequalities). Let the set of circular obstacles be \(\mathcal{O}=\{(c_j,r_j)\}_{j=1}^{n_{\text{obs}}}\) with centers \(c_j=[c_{x,j},c_{y,j}]^\top\) and radii \(r_j>0\). We require the robot’s position to stay outside each inflated disk of radius \(r_j+\delta\) (safety margin \(\delta\ge 0\)) at every knot:

\[

\underbrace{(p_{x,k}-c_{x,j})^2 + (p_{y,k}-c_{y,j})^2}_{\text{dist}^2(x_k,\text{center}_j)}

\;\;\ge\;\; (r_j+\delta)^2,

\qquad

\forall k=0,\dots,N,\ \forall j.

\]

In “\(c(x)\le 0\)” form (e.g., for fmincon):

\[

c_{j,k}(x_k) \;:=\; (r_j+\delta)^2 - \big((p_{x,k}-c_{x,j})^2 + (p_{y,k}-c_{y,j})^2\big) \;\le\; 0.

\tag{4.63}

\]

(iv) Simple bounds. Box limits on controls (and possibly states): \[ v_{\min} \le v_k \le v_{\max},\qquad \omega_{\min} \le \omega_k \le \omega_{\max},\qquad k=0,\dots,N-1. \tag{4.64} \]

Objective function. We use a smooth quadratic objective combining (a) terminal goal tracking, (b) control effort, and (c) control smoothness (temporal regularization):

- Terminal goal tracking to a desired pose \(B=[p_x^\star,p_y^\star,\theta^\star]^\top\): \[ J_{\text{goal}} \;=\; w_{\text{pos}} \,\big\|x_N^{\text{pos}} - B^{\text{pos}}\big\|_2^2 \;+\; w_{\theta}\,(\theta_N-\theta^\star)^2, \quad x_N^{\text{pos}}=[p_{x,N},p_{y,N}]^\top. \]

- Control effort: \[ J_{u} \;=\; \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} w_u \,\|u_k\|_2^2 \;=\; \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} w_u\,(v_k^2+\omega_k^2). \]

- Control smoothness (discrete total-variation-like quadratic): \[ J_{\Delta u} \;=\; \sum_{k=0}^{N-2} w_{\Delta u}\,\|u_{k+1}-u_k\|_2^2. \]

The complete cost is \[ J(x_{0:N},u_{0:N-1}) = \frac{1}{2}\Big( J_{\text{goal}} + J_u + J_{\Delta u} \Big), \tag{4.65} \] where the outer factor \(\frac{1}{2}\) is conventional in quadratic objectives.

Complete optimization problem. Given \(A,B,\{(c_j,r_j)\},\delta,h,N\), choose \(\{x_k\}_{k=0}^N,\{u_k\}_{k=0}^{N-1}\) to \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{\{x_k,u_k\}} \quad & \frac{1}{2}\Big( w_{\text{pos}} \|x_N^{\text{pos}}-B^{\text{pos}}\|_2^2 + w_{\theta}(\theta_N-\theta^\star)^2 + \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} w_u \|u_k\|_2^2 + \sum_{k=0}^{N-2} w_{\Delta u} \|u_{k+1}-u_k\|_2^2 \Big) \\[2mm] \text{s.t.}\quad & x_0 = A, \\[2pt] & x_{k+1} = f_h(x_k,u_k)\quad \text{for } k=0,\dots,N-1, \\[2pt] & (r_j+\delta)^2 - \big((p_{x,k}-c_{x,j})^2 + (p_{y,k}-c_{y,j})^2\big) \le 0, \ \ \forall j,\ \forall k, \\[2pt] & v_{\min} \le v_k \le v_{\max},\quad \omega_{\min} \le \omega_k \le \omega_{\max},\quad k=0,\dots,N-1. \end{aligned} \] This is a smooth, sparse nonlinear program (NLP).

Experimental setup.

- Horizon \(N=60\), step \(h=0.1\) s.

- Start \(A=[0,0,0]^\top\), goal \(B=[6,5,0]^\top\).

- Obstacles \(\{(c_j,r_j)\}\) with a margin \(\delta=0.25\) m.

- Control bounds \(v\in[-1.5,1.5]\) m/s, \(\omega\in[-2,2]\) rad/s.

- Weights \(w_{\text{pos}}=400,\ w_\theta=20,\ w_u=0.05,\ w_{\Delta u}=0.2\).

- Initialization: straight-line interpolation of positions from \(A\) to \(B\), heading toward the line, constant \(v\), \(\omega=0\).

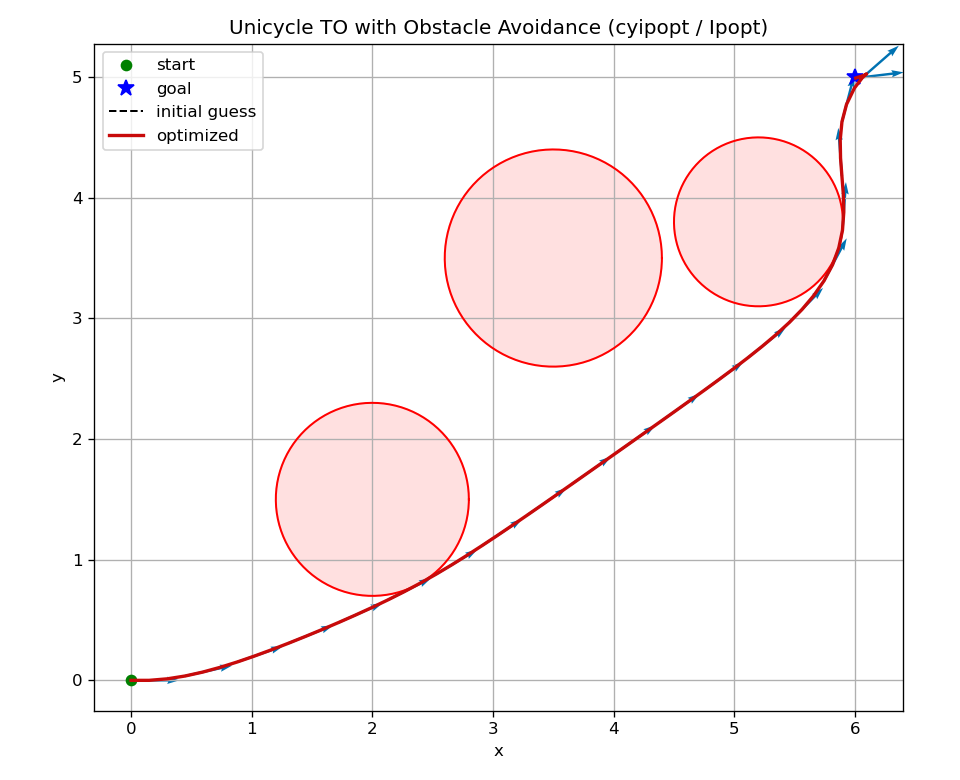

Two obstacles (success). Fig. 4.6 shows the results for trajectory optimization with two obstacles. As we can see, the SQP algorithm generates a smooth trajectory that avoids the two circular obstacles, despite the fact that the initial guess crosses both obstacles.

Figure 4.6: Trajectory optimization for unicyle using SQP (two obstacles). Dotted line: initial guess; solid line: optimized trajectory.

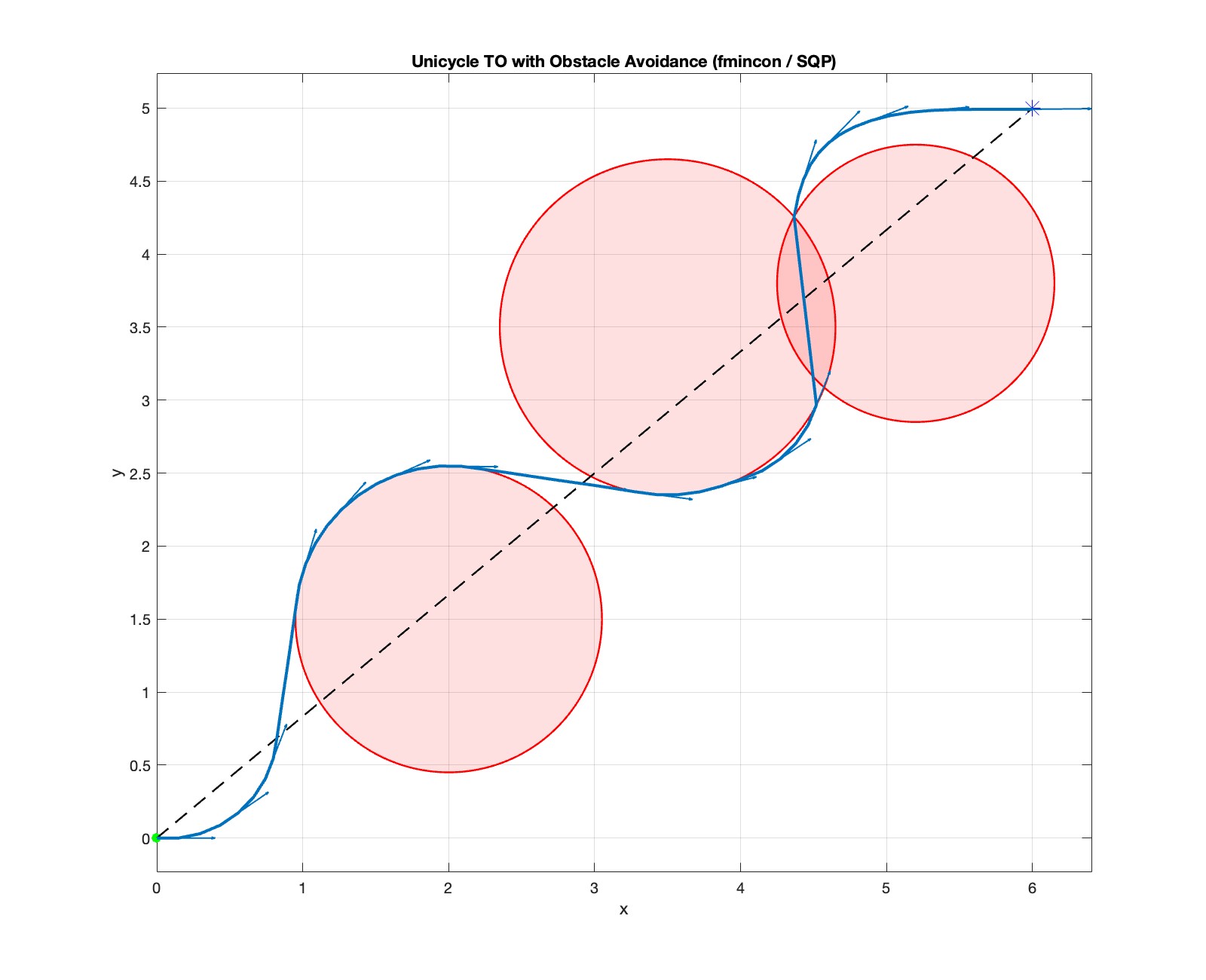

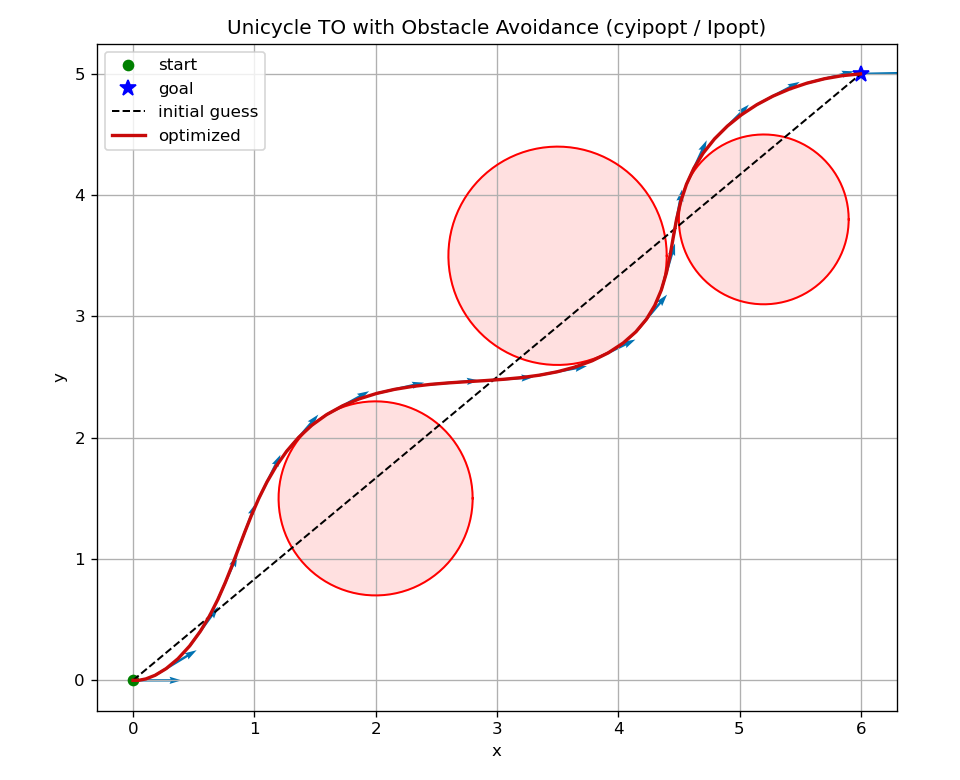

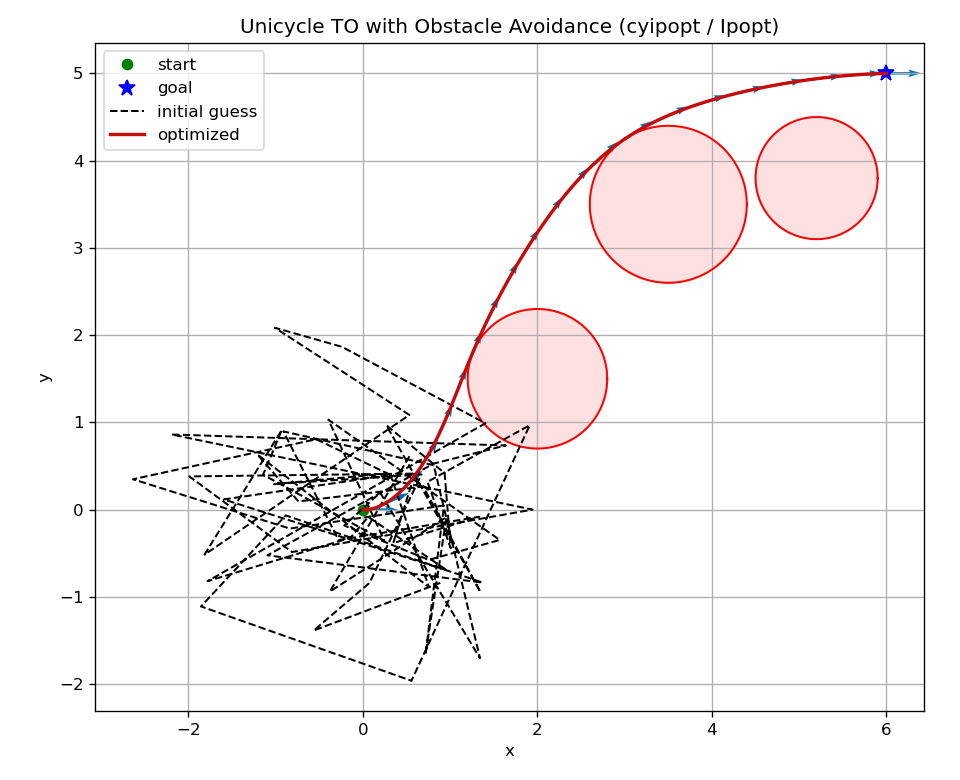

Three obstacles (failure). However, when we add a third obstacle, Fig. 4.7 shows that the SQP algorithm converges to an infeasible solution that collides with the obstacles.

You can play with the Matlab code here.

Figure 4.7: Trajectory optimization for unicyle using SQP (three obstacles). Dotted line: initial guess; solid line: optimized trajectory.

The example above highlights both the strengths and the limitations of solving TO with numerical NLP methods such as SQP. Because the TO problem is generally nonconvex, a local method’s outcome depends strongly on the initialization. With a good initial guess, local NLP solvers often converge quickly to a high-quality solution (e.g., Fig. 4.6). With a poor initialization—especially when the landscape has many local minima—the solver may settle in a suboptimal basin or even fail to find a feasible trajectory (e.g., Fig. 4.7).

Global optimization methods can avoid initialization sensitivity and provide global optimality guarantees. These techniques can be substantially more expensive and require additional structure or reformulation, but when applicable they yield powerful initialization-free solutions; see, e.g., (Kang et al. 2024) and references therein.

4.3.5 Interior-Point Methods

We have seen that Primal–Dual Interior-Point Methods (PD-IPM) efficiently solve convex QPs (Section 4.3.3). The key idea was to write the KKT optimality conditions as a system of nonlinear equations and apply Newton’s method. We now extend this idea to the general NLP in (4.55): \[ \min_{x\in\mathbb{R}^n} f(x)\quad\text{s.t.}\quad c(x)=0,\;\; d(x)\le 0, \] where \(f:\mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}, c:\mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^m\) and \(d:\mathbb{R}^n \to\mathbb{R}^p\) are smooth.

4.3.5.1 Lagrangian and KKT

Introduce slack variables \(s\in\mathbb{R}^p\) to convert inequalities to equalities: \[ c(x)=0,\qquad d(x)+s=0,\qquad s\ge 0. \tag{4.66} \]

With equality multipliers \(y\in\mathbb{R}^m, \nu \in \mathbb{R}^p\) and inequality multipliers \(\mu\in\mathbb{R}^p\) (with \(\lambda \ge 0\)), the Lagrangian of the slack-form problem is \[ \mathcal L(x,s,y,\nu,\lambda) \;=\; f(x) + y^\top c(x) + \nu^\top \big(d(x)+s\big) - \lambda^\top s. \tag{4.67} \]

The KKT optimality conditions are (after eliminating \(\nu\)) \[ \begin{aligned} \text{stationarity:}&\quad \nabla f(x) + J_c(x)^\top y + J_d(x)^\top \lambda = 0,\\ \text{primal feasibility:}&\quad c(x)=0,\;\; d(x)+s=0,\;\; s\ge 0,\\ \text{dual feasibility:}&\quad \lambda\ge 0,\\ \text{complementarity:}&\quad s_i\,\lambda_i = 0,\quad i=1,\dots,p, \end{aligned} \tag{4.68} \] where \(J_c=\nabla c(x) \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}\), \(J_d=\nabla d(x) \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times n}\).

4.3.5.2 Two Equivalent Views

There are two equivalent ways to derive primal–dual IPMs.

Homotopy / Perturbed KKT (primal–dual view). Replace the complementarity slackness condition in the KKT system (4.68) by a perturbed relation that defines the central path: \[ S\,\lambda \;=\; \mu \,\mathbf{1},\qquad S:=\operatorname{diag}(s),\;\; \mu >0. \tag{4.69} \] Driving the parameter \(\mu \downarrow 0\) yields iterates approaching a KKT point.

Barrier (log-barrier view). Solve the barrier subproblem \[ \min_{x,s>0}\; f(x) - \mu \sum_{i=1}^p \log s_i \quad\text{s.t.}\quad c(x)=0,\;\; d(x)+s=0, \tag{4.70} \] then reduce \(\mu\). The KKT conditions of (4.70) imply \(S\lambda = \mu \mathbf{1}\), hence the barrier and homotopy views are equivalent (different perspectives on the same central path).

4.3.5.3 Primal–Dual Residuals and Newton System

Define residuals at \((x,s,y,\lambda)\): \[ \begin{aligned} r_{\mathrm{dual}} &= \nabla f(x) + J_c^\top y + J_d^\top \lambda,\\ r_{\mathrm{pe}} &= c(x),\\ r_{\mathrm{pi}} &= d(x)+s,\\ r_{\mathrm{cent}} &= S\lambda - \mu \,\mathbf{1}. \end{aligned} \tag{4.71} \] Let \[ H \;:=\; \nabla^2_{xx}\mathcal L(x,s,y,\lambda) = \nabla^2 f(x) + \sum_{i=1}^m y_i \nabla^2 c_i(x) + \sum_{j=1}^p \lambda_j \nabla^2 d_j(x) \tag{4.72} \] be the exact Hessian of the Lagrangian with respect to \(x\).

A primal–dual Newton step \((\Delta x,\Delta s,\Delta y,\Delta \lambda)\) solves \[ \begin{aligned} H\,\Delta x + J_c^\top \Delta y + J_d^\top \Delta \lambda &= -\,r_{\mathrm{dual}},\\ J_c\,\Delta x &= -\,r_{\mathrm{pe}},\\ J_d\,\Delta x + \Delta s &= -\,r_{\mathrm{pi}},\\ S\,\Delta \lambda + M\,\Delta s &= -\,r_{\mathrm{cent}},\qquad M:=\operatorname{diag}(\lambda). \end{aligned} \tag{4.73} \]

Eliminating \(\Delta s=-r_{\mathrm{pi}}-J_d\Delta x\) gives \[ \Delta \lambda = S^{-1}\!\left(-r_{\mathrm{cent}} + M\,r_{\mathrm{pi}} + M\,J_d\,\Delta x\right). \tag{4.74} \] Substitute into the first line to obtain the reduced symmetric system in \((\Delta x,\Delta y)\): \[ \begin{bmatrix} H + J_d^\top D\,J_d & J_c^\top\\[2pt] J_c & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}\Delta x\\ \Delta y\end{bmatrix} = - \begin{bmatrix} r_{\mathrm{dual}} + J_d^\top S^{-1}\!\big(-r_{\mathrm{cent}} + M r_{\mathrm{pi}}\big)\\[2pt] r_{\mathrm{pe}} \end{bmatrix} \tag{4.75} \] with \(D:=S^{-1}M\). Then recover \(\Delta \lambda\) via (4.74) and \(\Delta s=-r_{\mathrm{pi}}-J_d\Delta x\).

4.3.5.4 Line-search IPM

Step lengths (fraction-to-the-boundary). Choose positive step sizes that keep strict interiority: \[ \alpha_{\mathrm{pri}}=\min\!\Big(1,\ \eta \min_{\Delta s_i<0}\frac{-s_i}{\Delta s_i}\Big),\quad \alpha_{\mathrm{du}} =\min\!\Big(1,\ \eta \min_{\Delta \lambda_i<0}\frac{-\lambda_i}{\Delta \lambda_i}\Big),\quad \eta\in(0,1). \tag{4.76} \]

Merit (or filter) globalization. Use a barrier merit for backtracking, \[ \Phi_{\mu}(x,s) \;=\; f(x) - \mu \sum_i \log s_i + \frac{\rho}{2}\,\|c(x)\|_2^2 + \frac{\rho}{2}\,\|d(x)+s\|_2^2, \tag{4.77} \] or a filter that accepts steps reducing either infeasibility or the barrier objective.

Mehrotra predictor–corrector (recommended).

Predictor (affine) step: solve (4.75) with \(\mu=0\) to get \((\Delta x^{\mathrm{aff}},\Delta s^{\mathrm{aff}},\Delta y^{\mathrm{aff}},\Delta\lambda^{\mathrm{aff}})\), and affine step sizes \(\alpha_{\mathrm{pri}}^{\mathrm{aff}},\alpha_{\mathrm{du}}^{\mathrm{aff}}\).

Centering: set \[ \tau_{\mathrm{aff}}=\frac{(s+\alpha_{\mathrm{pri}}^{\mathrm{aff}}\Delta s^{\mathrm{aff}})^\top (\lambda+\alpha_{\mathrm{du}}^{\mathrm{aff}}\Delta\lambda^{\mathrm{aff}})}{p},\qquad \sigma=\left(\frac{\tau_{\mathrm{aff}}}{\frac{s^\top\mu}{p}}\right)^{3}, \] and replace the complementarity RHS by \(\mu=\sigma\,\frac{s^\top\lambda}{p}\).

Corrector: resolve (4.75) with the corrected central residual \[ r_{\mathrm{cent}}^{\mathrm{corr}} = S\lambda - \mu \,\mathbf{1} - \Delta S^{\mathrm{aff}}\Delta\lambda^{\mathrm{aff}}\mathbf{1}. \tag{4.78} \]

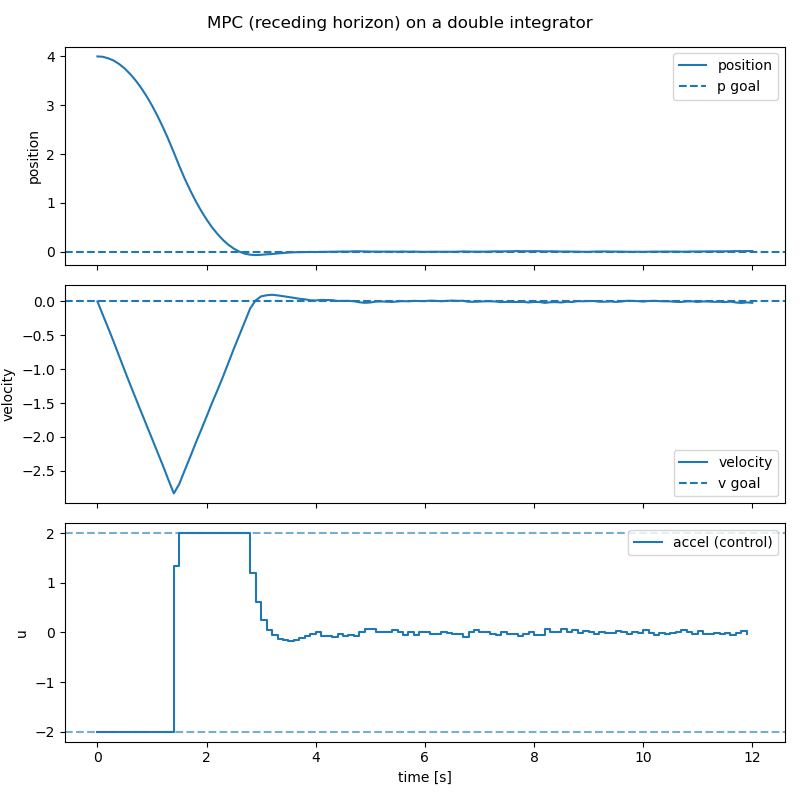

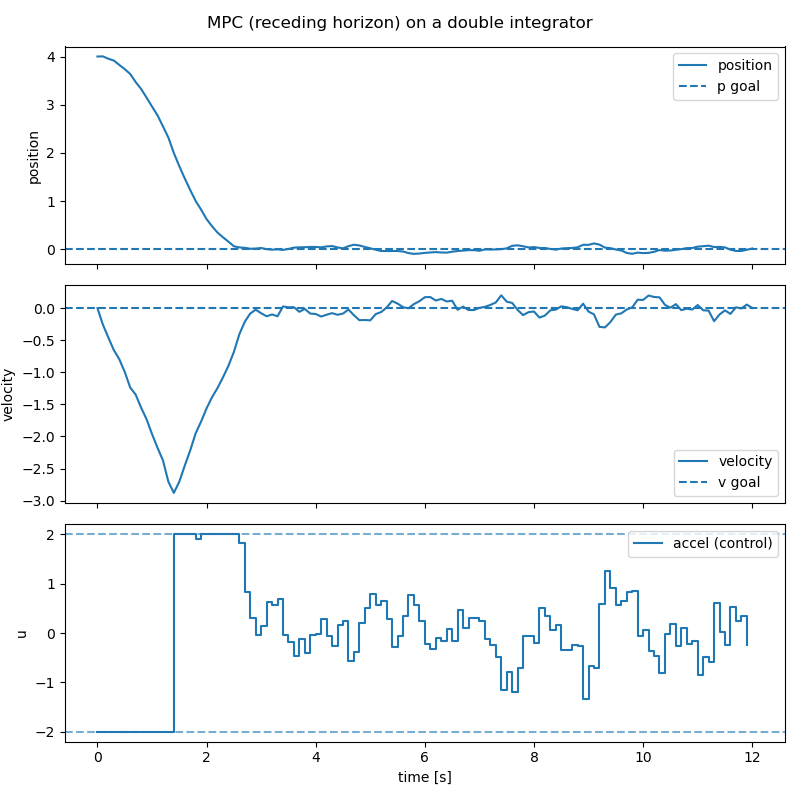

Line search & update: use (4.76) and backtrack on \(\Phi_{\mu}\).